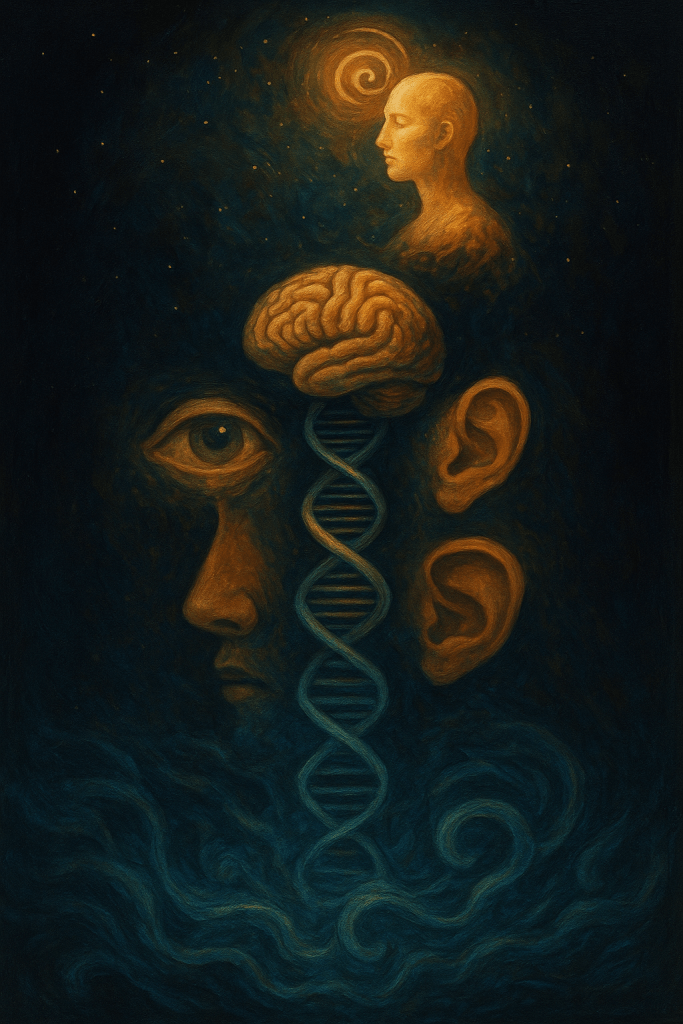

Exploring the dialogue between brain, being, and the pursuit of wholeness

Author’s Note

This essay is part of an ongoing exploration into the evolution of human consciousness — a synthesis of neuroscience, depth psychology, and symbolic archaeology. It traces how our perception, shaped by the hemispheric balance of the brain, has evolved from the mythic to the analytical, from the cave wall to the temple pillar. Through this unfolding, I seek to illuminate the dialogue between cognition and meaning — and the quiet possibility of equilibrium that awaits beyond our modern fragmentation.

Introduction

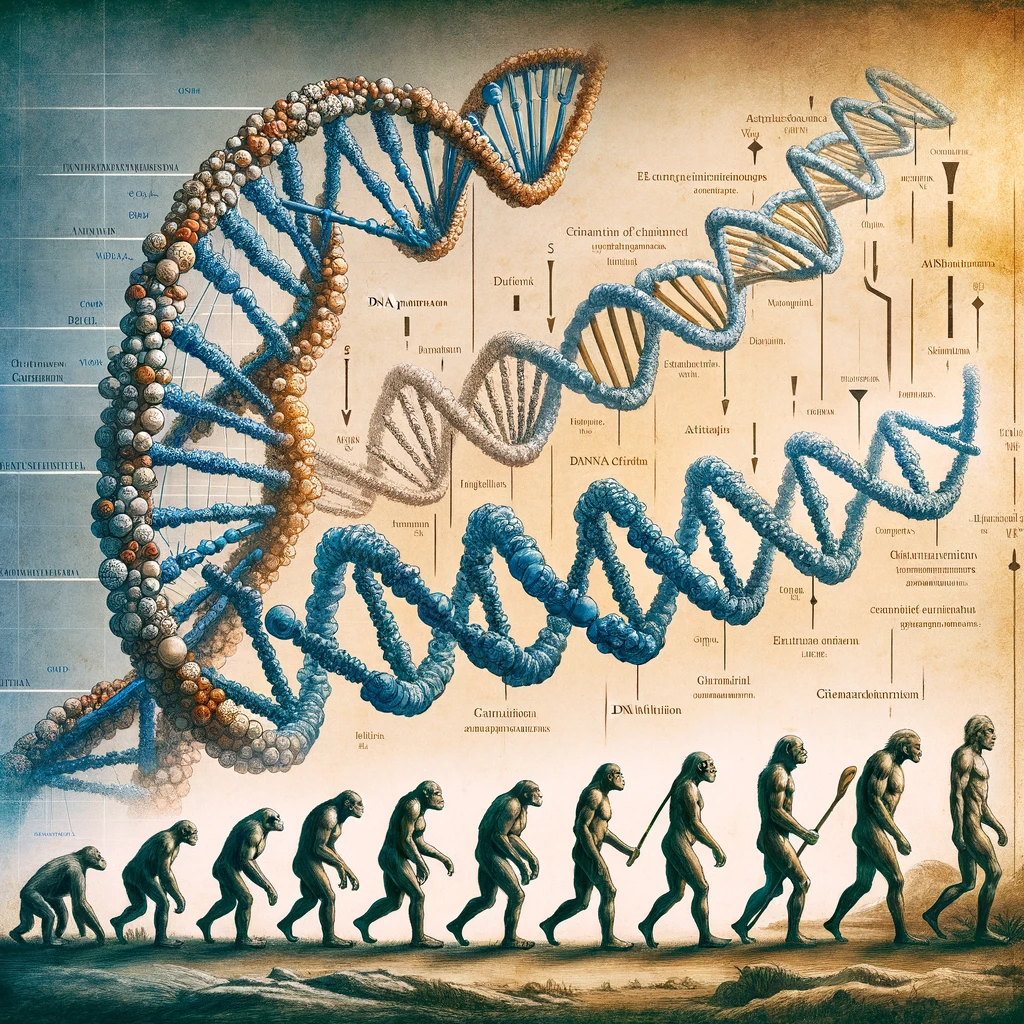

Throughout humanity’s evolutionary history, shifts in both intelligence and perception have occurred, often following periods of environmental upheaval. These shifts were products of novel adaptive strategies that caused incremental adjustments in cognition — the result of reoriented neural pathways and the activation of dormant genes. After thousands of years of implementing these adaptive strategies, humanity began to experience abrupt increases in both intelligence and perception (Libedinsky et al., 2025; Sánchez Goñi, 2020).

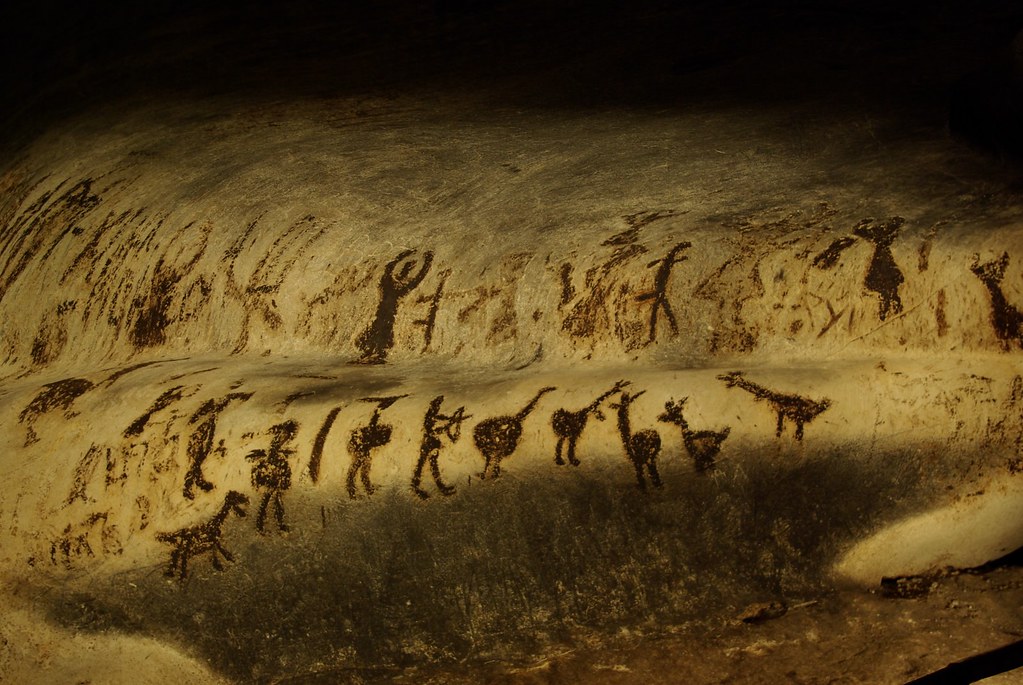

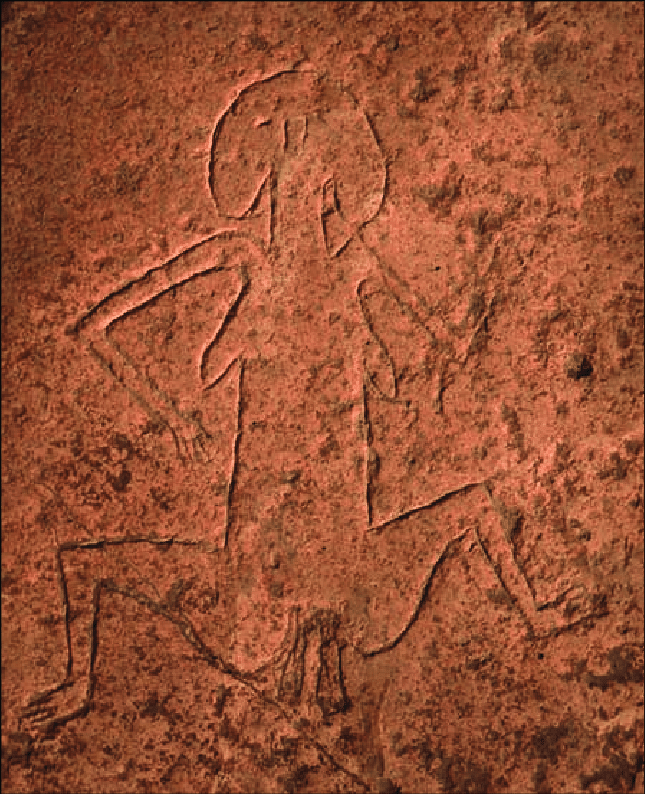

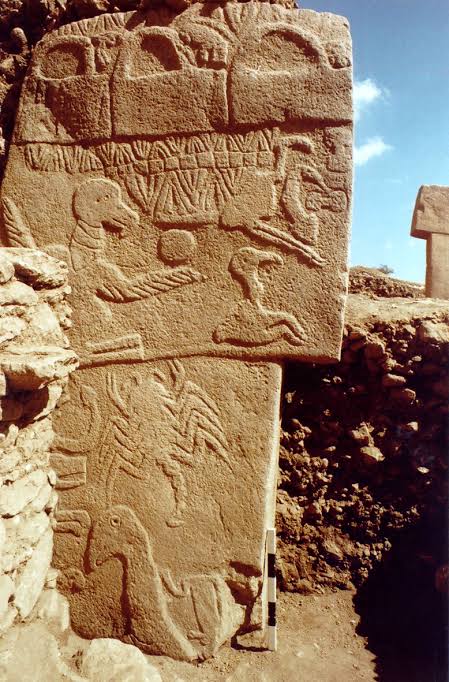

Such abrupt changes become increasingly evident as humanity progressed through more recent epochs, particularly from the Paleolithic to modern times. These shifts are visible throughout the Paleolithic period, when art first became a prominent practice among prehistoric peoples (Aubert et al., 2019; Srivastava, 2020). The Neolithic period then introduced dramatic innovations — megalithic structures, agriculture and herding, improved weaponry, and the formation of coherent religious systems (Cauvin, 2000; Schmidt, 2010). Each stage of development only refined these capacities, advancing precision and clarity in every domain.

Precision and clarity appear to be the hallmarks of enhanced cognition — and with them, the necessity for systemization. Why? Because both arise from neuroanatomical shifts and the intrinsic nature of curiosity. Three fundamental facets of this precise, systemized orientation are evident: cohesion, functionality, and progression. These facets apply not only to society but to the individual psyche as well.

Neuroanatomical Shift

Since humans and chimpanzees diverged from a last shared common ancestor approximately six million years ago, our brains have increased substantially in size and complexity. A major leap occurred in our transition from Australopithecus to Homo erectus some 2.2 million years ago — a near doubling in brain size. From there, expansion continued, reaching its peak with Neanderthals (Püschel et al., 2024).

With the emergence of Homo sapiens, however, a new trend appeared: instead of expanding in size, the brain increased in capacity. This efficiency is evident in the greater number of neurons within the human neocortex, particularly the frontal lobe — the seat of critical and complex thinking (Pinson et al., 2022).

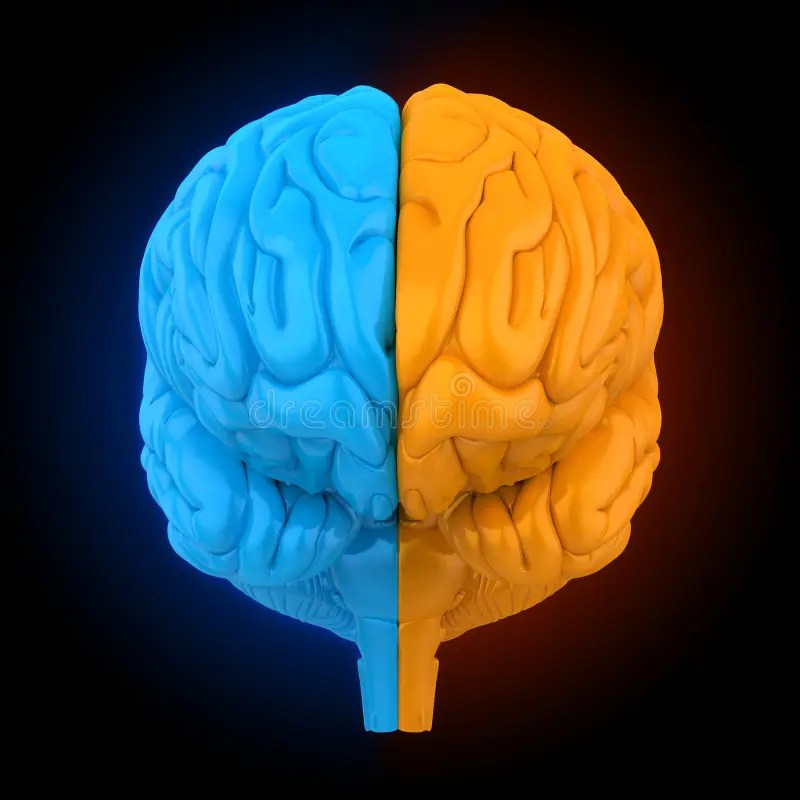

Along with this cognitive refinement came a shift in hemispheric utility. McGilchrist (2019) revealed a fundamental distinction between right and left hemispheric modes of attention: the right perceives the world holistically and peripherally, while the left seeks precision and control. The right is imaginative and integrative; the left, analytical and categorical.

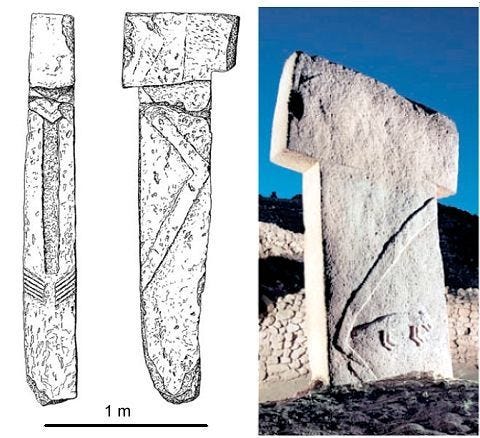

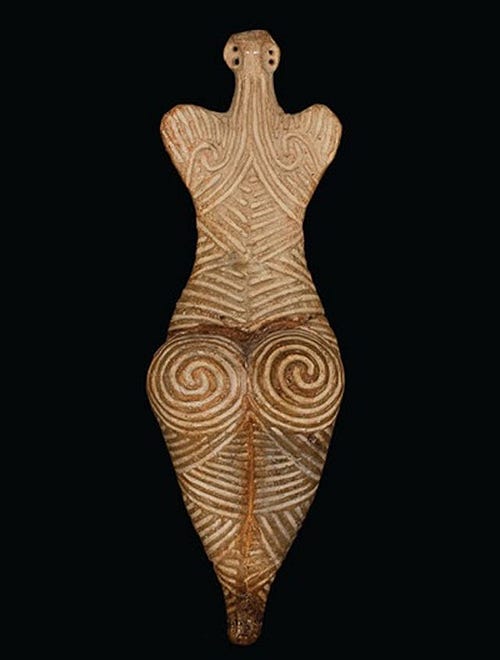

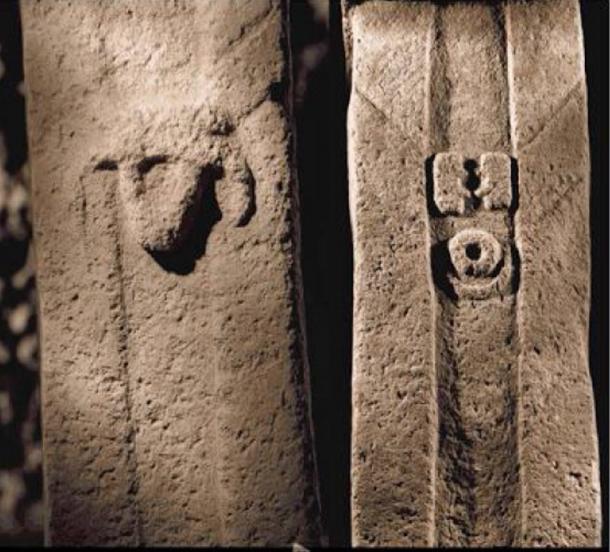

Humanity began moving toward the left-hemispheric mode in the Paleolithic era, with the introduction of artistic design. The precision required for symbolic expression suggests the growing involvement of the left hemisphere. This subtle reliance increased into the Neolithic, visible in the construction of monumental architecture, agricultural organization, and the emergence of figurative representation.

Sites such as Göbekli Tepe and Jericho exemplify this shift: architectural precision, sustainable agriculture, and the differentiation of male and female figurines all point toward the rising influence of left-hemispheric categorization (Cauvin, 2000; Schmidt, 2010).

As time progressed, this categorical and precise mode continued to shape civilization. Technological innovations, religious institutions, and hierarchical social structures all attest to an increasing dominance of left-hemispheric perception. At the heart of this development lies an enduring human trait — curiosity.

Human Curiosity

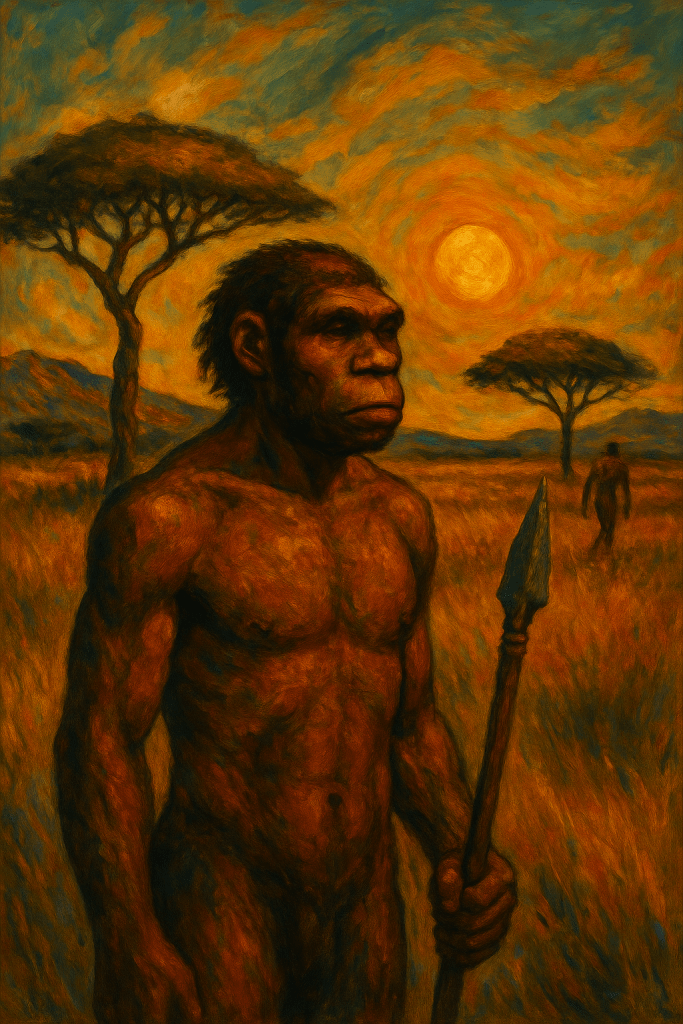

Curiosity has characterized human behavior since Homo erectus first migrated out of Africa nearly two million years ago (Bae & Manthey, 2025). Scrivner (2022) suggests that curiosity is an adaptive trait that enables humans to better navigate and understand their environment. This exploratory impulse fosters innovation — whether objective or subjective — as humanity continually seeks to improve its condition.

Whether driven by novelty-seeking or the desire to comprehend the unknown, humanity possesses an intrinsic longing to explore and apprehend (Scrivner, 2022). This propensity intensifies across millennia, especially as intelligence increases. Curiosity, as a facet of openness to experience, is strongly correlated with higher intelligence (Schretlen et al., 2010).

As intelligence evolved, so too did the desire to categorize the world for comprehension and control. This drive likely coincided with increased left-hemispheric engagement — the side that dissects, defines, and organizes reality.

Yet this same curiosity that propelled humanity forward can, if left unchecked, create imbalance. McGilchrist (2019) warns of pathological left-hemispheric dominance — an overreliance on precision that excludes wholeness. I seek to extend his observation through a deeper evolutionary lens.

Appreciation and Apprehension

From tools, art, and fire to agriculture and megaliths, humanity has long sought to understand both itself and the cosmos. This expanding apprehension culminated in hierarchical institutions, complex governments, and meaning-oriented religious systems — each amplifying the role of the left hemisphere (Cauvin, 2000; McGilchrist, 2019).

As with all pursuits, there are trade-offs. Precision and clarity have provided coherence to the human story, but often at the cost of individuality. Categorization enhances cohesion and efficiency, yet risks stripping humanity of freedom. Progress achieved collectively can impede the growth of the individual soul.

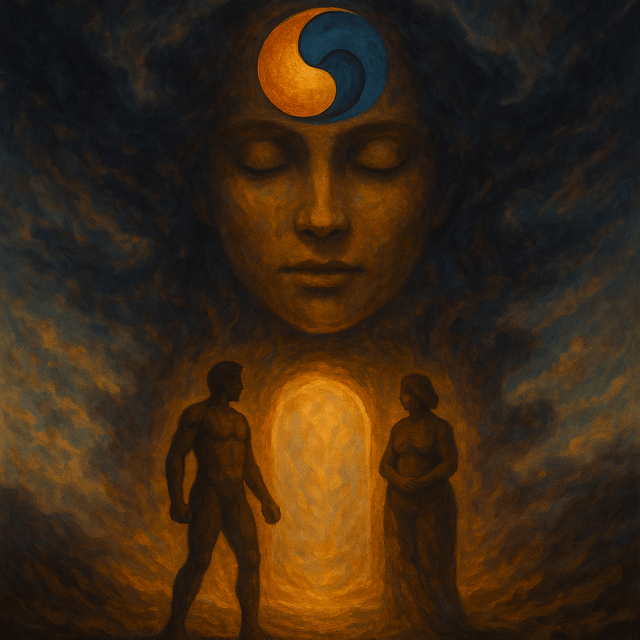

These trade-offs echo the state of modern society — an era that privileges institutional functionality over personal meaning. Trade-offs are inevitable in nature; however, they can be harmonized rather than polarized. McGilchrist (2019) proposes a necessary return to right-hemispheric balance — not by abolishing the left, but by restoring the dialogue between them.

Such equilibrium parallels Jung’s process of individuation — a dynamic oscillation between the ego (left hemisphere) and the collective unconscious (right hemisphere) (Jung, 1956). Through this process, both society and self can move toward a state of wholeness.

A civilization that helps each individual integrate these hemispheric and psychological opposites will foster empathy, creativity, and renewal. Through the interplay of apprehension and appreciation, humanity may yet rediscover equilibrium — and in doing so, usher in the next phase of evolution: the evolution of consciousness itself.

May we learn again to see with both eyes of the mind — one of reason, and one of wonder.

— Michael Thacker

References:

Aubert, M., Lebe, R., Oktaviana, A. A., Tang, M., Burhan, B., Hamrullah, Jusdi, A., Abdullah, Hakim, B., Zhao, J. X., Geria, I. M., Sulistyarto, P. H., Sardi, R., & Brumm, A. (2019). Earliest hunting scene in prehistoric art. Nature, 576(7787), 442–445. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1806-y

Bae, C.J. & Manthey, C. (2025). Out of Africa I revisited: Life history, energetics, and the evolutionary capacity for early hominin dispersals, Quaternary Science Reviews, 370, ISSN 0277-3791, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2025.109690.

Cauvin, J. (2000). The birth of the gods and the origins of agriculture. Cambridge University Press.

Jung, C. (1956). Symbols of transformation. Princeton University Press.

Libedinsky, I., Wei, Y., de Leeuw, C., Rilling, J. K., Posthuma, D., & van den Heuvel, M. P. (2025). The emergence of genetic variants linked to brain and cognitive traits in human evolution. Cerebral cortex, 35(8), bhaf127. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhaf127

McGilchrist, I. (2019). The master and his emissary. Yale University Press.

Pinson, A., Xing, L., Namba, T., Kalebic, N., Peters, J., Oegema, C. E., Traikov, S., Reppe, K., Riesenberg, S., Maricic, T., Derihaci, R., Wimberger, P., Pääbo, S., & Huttner, W. B. (2022). Human TKTL1 implies greater neurogenesis in frontal neocortex of modern humans than Neanderthals. Science (New York, N.Y.), 377(6611), eabl6422. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abl6422

Püschel, T.A., Nicholson, S.A., Baker, J., Barton, R.A. & Venditti., C. (2024). Hominin brain size increase has emerged from within-species encephalization, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 121 (49) e2409542121, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2409542121

Sánchez Goñi, M. F. (2020). Regional impacts of climate change and its relevance to human evolution. Evolutionary Human Sciences, 2, e55. https://doi.org/10.1017/ehs.2020.56

Scrivner, C. (2024). Curiosity: A behavioral biology perspective’, in Laith Al-Shawaf, and Todd K. Shackelford (eds), The Oxford handbook of evolution and the emotions. Oxford Publications. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197544754.013.20

Schmidt, K. (2010). Göbekli Tepe – the Stone Age Sanctuaries. New results of ongoing excavations with a special focus on sculptures and high reliefs. Documenta Praehistorica, 37, 239-256. https://doi.org/10.4312/dp.37.21

Schretlen, D. J., van der Hulst, E. J., Pearlson, G. D., & Gordon, B. (2010). A neuropsychological study of personality: trait openness in relation to intelligence, fluency, and executive functioning. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology, 32(10), 1068–1073. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803391003689770