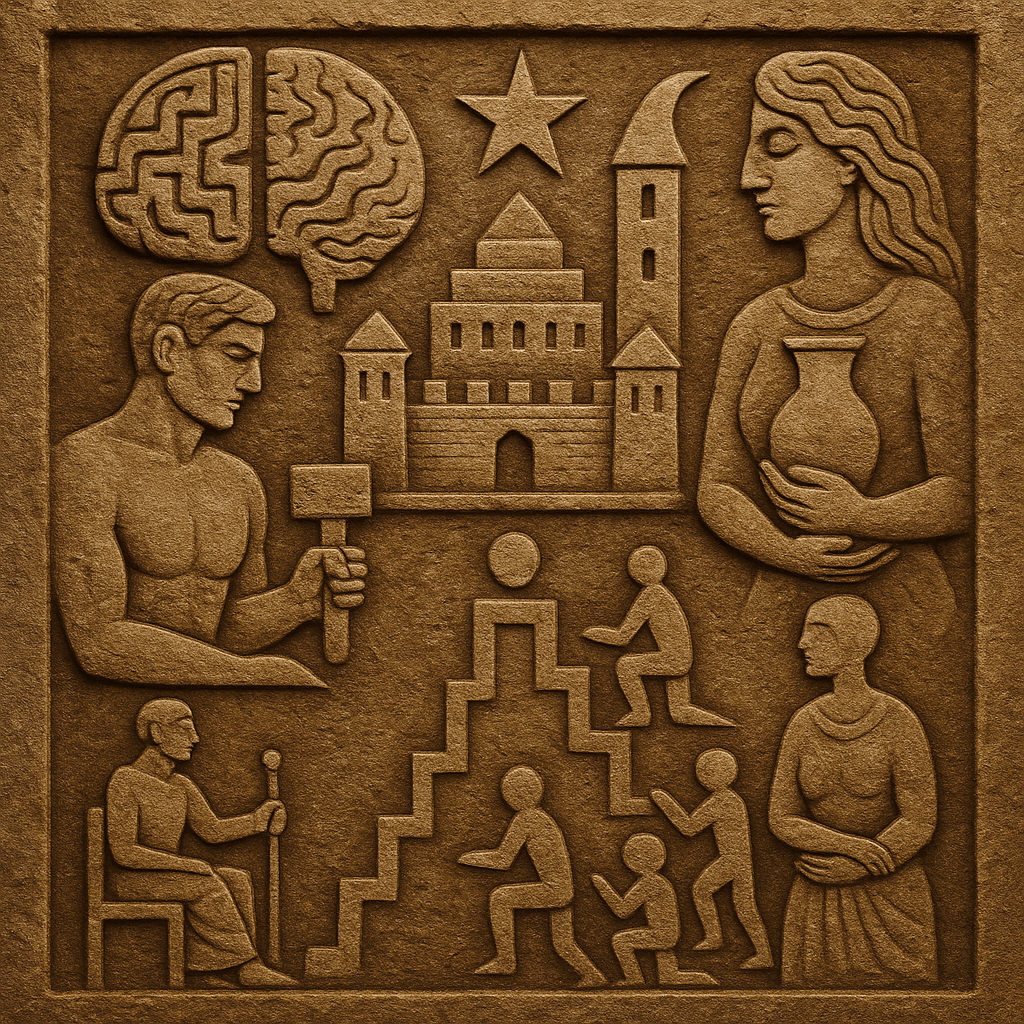

“Tracing How Civilization, Hierarchy, and Technology Shaped the Modern Landscape of Gender”

Author’s Note:

This series examines how evolutionary pressures, psychological development, and cultural transformation collectively shaped the modern relationship between the sexes. Part II continues this investigation by exploring the rise of civilization, the construction of hierarchy, and the technological and ideological forces that reshaped gender dynamics across millennia.

Read Part One Here: Evolutionary Foundations of Sex Differences – Michael Thacker

Civilization and the Construction of the Ego

Throughout the Neolithic period, two important transformations of humanity can be observed that only increased substantially with the emergence of civilization. First, an increase in left-hemisphere utilization is evident beginning with the construction of the first megalithic structure of Göbekli Tepe. The left hemisphere’s desire to apprehend the world is accomplished here by the manipulation of material used in construction and the construction process itself. This left-hemispheric leaning tendency is further observed in the apprehension of plants and animals a few centuries later.

Next, ego development among the collective. For Jung, the ego is identified as the innermost conscious part of the overarching Self. Within this structure reside identity, personality, and self-awareness, which are then expressed through being. It is only by differentiating the ego from the collective unconscious that an individual, as well as the collective, can develop an authentic sense of self (Jung, 1956; Neumann, 1954). This developmental process of the psyche parallels — neurologically — the increased reliance on the left hemisphere (McGilchrist, 2019).

As the millennia unfolded, both the ego and left hemisphere developed further, and with this development came greater understanding of the human condition and the need for survival. The representation of such can be found in the symbolic figurines of Venus and the bull, which later increased in precise details around 7,000 years ago. Thus, these two were differentiated from an ambiguous form into male and female deities — a symbolic representation of the collective attempt at ego development.

This developmental trend was also evident in Neolithic architectural change. In the early period, ancient people designed their houses in circular or oval formations — a design that echoes the psychic representation of the collective unconscious (i.e., the ouroboros). However, this design transformed in the later period into straight, precise rectangular or square architecture. Again, signaling an increase in left-hemispheric reliance (Cauvin, 2000).

Beginning approximately 6,000 years ago, tribes located in and around the Fertile Crescent began to form alliances. This increase in cooperation and manpower helped establish the world’s first society — an evolutionary process that was occurring almost simultaneously in Egypt.

These new societies brought with them the construction of massive structures. Towering pyramids were built in Egypt while ziggurats were the step pyramids of Sumeria. Cities were constructed with buildings such as schools, markets, and governmental facilities, with streets that connected throughout and beyond — infrastructure that provided safety and stability for all its inhabitants.

With these stable infrastructures came a greater need for cooperation through conformity. Since it was men who did most, if not all, of the construction of these infrastructures, they were those by whom conforming ideals were manufactured — ideals that were first implicit only to later become explicit with the emergence of writing (Giosan & Goodman, 2025).

The first explicit manifestation of conformity was produced by King Ur-Nammu of Ur in the third millennium BC (2100 BC), legalistic in formality. As laws progressed and spread outward to other regions that established their own societies, such as Canaan, Greece, and India, they became intrinsically integrated with religious narratives. These narratives exemplified the human condition, including the process of ego development — formally illustrated in ancient Babylon in the story of Marduk and Tiamat (Neumann, 1954).

These conforming measures provided further structure for these new societies, and with them also came a hierarchical system. Though tyrannical in their essence, hierarchical systems improve functionality when everyone contributes according to their specified domain. Each domain is categorized according to an individual’s physical and cognitive ability. Those near the top handle issues pertaining to higher cognitive needs, while those toward the bottom require less cognitive effort yet more physical power.

Though hierarchies can provide benefits such as structure and improved efficiency, they can become tyrannical. One means of achieving this tyrannical state is through psychopathic individuals forcing their way into positions of power. This corrupts the system through a top-down means where most, if not all, of the power is situated near the top.

Another way tyranny emerges in hierarchical systems is through rigidity of the functional components themselves — a lack of communication and cooperation that results in each tier retaining its functional qualities for itself. Consequently, the system collapses of its own accord.

The key to maintaining functional hierarchical structures lies in nourishing a left- and right-hemispheric equilibrium. The left hemisphere provides comprehension of the necessity of hierarchical structure and the purpose of each component. In parallel, the right hemisphere helps one perceive the contextual elements involved that contribute to the holistic function of the mechanism itself. Maintenance of this dichotomy is attained by integrating traditional elements with adaptable concepts. Both help sustain the structural integrity of individuals and social dynamics, while at the same time providing the essence by which these systems can gradually update in a coherent and structured fashion.

Regarding the ancient emergence of social order, one must bear in mind that this was a novel evolutionary phenomenon, so a bit of humility is due. With that said, the structure itself was not ideal — especially in the egalitarian sense. However, there are legitimate, as well as illegitimate, reasons for this inequity.

Legitimate reasons include the lack of technological commodities and the immense physical effort required of male participants. The former is often overlooked, even by academics. One of the primary reasons equality is embedded within the confines of modern society — besides the evolution of the intellectual capacity that led to this emergent concept — was technological advancement.

As mentioned in the introduction, feminism advanced laws; however, this is only part of the whole picture. The other, rather large, portion of the contextual framework that resulted in the emancipation of women was modernity. Technologies such as tampons, birth control, household appliances, and equipment that reduced the need for brute physical strength all contributed in major ways to the full participation of women in the broader context of society (Coen-Pirani et al., 2010; Goldin & Katz, 2002). The latter consideration is equally important — men were the primary power-movers by which early, and even modern, forms of civilization emerged. Without this will and strength, produced largely by higher testosterone levels, civilization most likely would have never been constructed. In modern times, technology has helped reduce differentiation between males and females, and has promoted equality of its own accord.

Therefore, the patriarchal order appeared — at least in its most explicit form — at the emergence of civilizations such as Sumer and Egypt some 6,000 years ago. It is also worth noting that the cooperation and collaboration between tribes that resulted in the formation of civilization were most likely accomplished by males — a common practice among modern hunter-gatherer tribes in Africa, South America, and Australia (Wrangham, 2019).

As civilization — and the hierarchical order within — evolved over time, so too did the propensity toward both forms of corruption mentioned previously. At various times throughout history, societies presented either a form of stagnation that inhibited communication and cooperation between hierarchical tiers, or all power and resources were funneled toward the upper end, or even a combination of the two. Again, these systems were evolving and thus not ideal; however, they helped contribute to an evolving concept of the ideal that has now provided humanity with what it currently possesses.

Modernity, Ideals, and the Pendulum of Perception

Civilization, along with its conceptual systems, again, is evolving. With that in mind, when analyzing these older systems, whether they be the hierarchical structure, conceptualized religious beliefs, or any other ethical framework, a dual perception must be utilized. These older systems were evolving alongside human consciousness — a phenomenological structure that had just recently emerged into perceptual clarity in the late Neolithic period. Therefore, empathy and grace are due for those that were conceptualizing and integrating such systems into society as it emerged.

However, this by no means excuses errors — either intentional or haphazard — resulting from our ancestors. What it does mean is that when analyzing such errors, instead of discriminating against such primitively evolving consciousness, one should rather seek to understand the nature of the faults. This is accomplished by acknowledging that one’s own discriminatory judgment is predicated on the successes and failures of these ancient people, and therefore some gratitude is due. When approached in humility, the underlying nature of these errors begins to emerge.

Instead of participating in criticism, it is best to seek the how and why these errors occurred in the first place. Though many in modern times do seek to explain these aspects of errors, they often do so in a simplistic, left-hemisphere-oriented fashion. Of course, as mentioned previously, this simplistic analysis is exactly the type of perception nested in privilege rather than humility.

To accomplish such an analysis of ancient ways, the how and why of these errors must be perceived in a manner that reflects ancient people’s developing consciousness. For example, the why and how of women’s rights during ancient times can be best understood by the evolving male ego. Though women contributed a great deal to the development of civilization through complementary labor, social cohesion, and textile development, men were the primary builders. This new society offered immense conveniences such as food, shelter, and safety. Thus, to participate in this new structure, one must adhere to the male-oriented codes that help sustain this structure.

Furthermore, these codes both protected and oppressed women. An excellent illustration of this is found in the Old Testament law wherein women were to be protected, while at the same time they were perceived as the property of men. The why to the protection aspect of these laws is due to the relative weakness of women compared to men at the time, especially in the absence of modern technology (something we will elaborate on here soon). However, these extra protective rights prompted men to also require extra privileges for themselves as well — men protected women in exchange for rights over them.

Now, does this justify such laws and behaviors of ancient people, especially that of men? This question is quite absurd when perceived in the manner of an evolving consciousness. Ancient people were experiencing rapid developments of consciousness that we now take for granted. What this means is that the perceptual systems of ancient people were still somewhat ambiguous and not fully coherent.

As time elapsed and knowledge expanded, so too did the development of the human psyche (consciousness). This is especially evident with the emergence of the eras of the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution. Both eras provided humanity with knowledge that had been previously concealed. The disclosure of novel information helped expand the perceptual model of humanity in such a way that allowed for a new form of consciousness to manifest.

With this new form of consciousness came the development of new discoveries of science and mathematics. Moreover, an explosion of artistic creativity occurred that depicted reality in intricate detail that was not formerly produced in ancient times. Writing, too, expanded rapidly in both fiction and nonfiction form in a variety of genres with a depth of quality not previously observed.

Likewise, the Industrial Revolution helped instigate technological innovation in ways that significantly enhanced humanity’s survival, and thus its apprehension of nature. These technologies provided conveniences that were alien to earlier humanity — improvements in transportation, advancements in medicine, increased material goods, and enhanced livability were of this sort.

However, just as these innovations and discoveries were alien to the ancient conscious mind, so too is the mode of being of these ancestors a mystery to us. For instance, rates of survival among ancient people were exceptionally low in comparison to us. Astoundingly, these rates continued in a marginal scale of improvement up until the 20th century wherein the rate of survival improved substantially thanks to many of the technological advancements mentioned prior.

It is partly — or perhaps more so — due to this need for astute perceptual emphasis on survival that much of the behavior of ancient, and even earlier, people was influenced. Prior to many of the modern technological conveniences, people lived in states of cooperative survival. Both men and women worked together to ensure the survival of their offspring and of one another — a phenomenon that may be more than 2 million years old. Furthermore, just as with intersex cooperation, intrasex collaboration was common between males and females as a form of expanded survival insurance. The dangers that these primitive people faced could only be partially romanticized and fantasized now.

As mentioned previously, this trend in perceptual emphasis on survival continued, at least to a certain degree, until the beginning of the 20th century. The majority of the population up until the 1940s and 1950s lived in poverty with low survival rates. For all intents and purposes, both men and women were oppressed and had to continue to work together to ensure the survival of their offspring and themselves. For example, most people in 19th century England lived on less than a dollar a day in accordance to modern standards (Allen, 2009; Hobsbawm, 1969). To be hungry and fatigued was an understatement.

Though both men and women were oppressed, men still fared better than women economically, especially regarding the top of the hierarchy. However, perceptual consideration is due at this point. Although men fared better than females economically, both the occupational roles and survival rates of men were far inferior to that of women historically speaking. Another example involves that of George Orwell (1937) when documenting the living and working conditions of early 20th century male coal mine workers in England. Here, Orwell noted that most men’s working environments were both exceptionally dangerous and detrimental to their health — many workers had no teeth and died from black lung at an early age, often in their 40s or 50s. This asymmetry created a superficial appearance of male privilege while masking the brutal survival demands placed disproportionately on men.

As technological advancements emerged within the social fabric of the “average” population, a coinciding decline in social oppressive qualities with improvements in survival rates occurred (National Research Council, 2011; Office for National Statistics, 2020). With these commodities came a reduction in the need for physical strength and thus helped reduce the quality and quantity of labor differences between men and women. These commodities also provided an increase in time and energy to be expended away from the need for survival and more time for leisure activities.

These two significant changes played a large role in the emancipation of women in modern times: the equalizing role of technologies and the increase in time and energy devotion. The former of these changes helped elevate women as equal within the confines of several industries, including administration, factory work, construction, and mechanical. Novel equipment that reduced the need for physical strength provided women the opportunity to participate in the same type of work as men. Prior to these advancements, the physical differences between men and women were too evident in many labor industries for women to participate in the same manner as men.

The latter of these two changes brought about a different means by which emancipation was made possible. With an increase in time and energy devotion, both men and women had the opportunity to disperse their energy towards things that intrigue them rather than just the sustenance needed for survival. However, during this development men and women sought to devote their extra time and energy towards different interests. Men often devoted themselves to leisure-type activities to help reduce the stress of labor, while women sought this opportunity to devote towards educating themselves and to promoting change.

Though inequality is a fundamental reason for the difference between these gender devotions, another reason for this difference can be found in labor itself. Men were not only the primary breadwinners on average in the early to mid-20th century, but they were also the ones that participated in the majority of physical labor. This type of energy expense prompted men to devote extra time to leisure activities to help decompress from the expense of labor. On the contrary, many women devoted to their homes still retained some vitality that they sought to devote towards the development of themselves and the female collective.

As mentioned in the previous section, men as a collective developed the ego through their construction of civilization. Though this development helped to significantly influence society towards its modern form, it also promoted a left hemisphere orientation that resulted in increased tyranny — the fundamental essence of the patriarchy. Women, unfortunately, received the short end of this developmental end.

However, beginning in the late 19th century and then increasing in vigor in the early 20th century, women began their own form of ego development. This does not mean that they were not developing themselves prior to; quite the contrary, the development of ego, and that of consciousness as a whole, has been occurring for millennia for both sexes prior to this time. Women only trailed behind men due to their protected nature that men provided prior to technological advancements. This protective measure inhibited ego development; however, a measure that was necessary nonetheless. Protection naturally limits self-differentiation — a pattern evident in both child development and cultural systems.

Modernity not only provided an equalized field for the participation of both men and women, but it also allowed for women to develop a sense of independence. This independence was transpired due to an environment that was now more conducive for women. No longer did women have to concern themselves with large predatory animals, natural phenomena, or, to a certain degree, the victims of predatory men. Though there is still some concern with the latter of these, overall male violence has substantially decreased over the past century and continues to do so.

It is this implicit independence that provided women with the necessary fundamental structure by which they could now move out into the world without the necessity of a man. In this new independence, women could officially begin the major shift in their collective ego development — a process that began with the rights to vote and pursue an education, major breakthroughs for women.

These momentous events for women paved the way for a new evolutionary trend for humanity that had never occurred before. Women no longer were obliged to conjoin with a man for survival — a feat that was now in the hands of both sexes. However, as with any process, there are both positive and negative consequences that must be considered. For instance, with the emancipation of women came a change in mate selection strategies that had been quite successful in the evolution of the human species for at least 7 million years if not longer.

Prior to this transformation, sexual selection was predicated upon women choosing mates that were higher up the hierarchy, thus providing access to resources that were often restricted for the higher-testosterone, highly driven men — those who were more vital and healthy. In exchange for these resources, women provided sexual and reproductive access for the man. This dynamic had been forever changed as women now played an equal role within the dominance hierarchy and thus provided themselves with access to these resources once restricted to the other sex. Bear in mind, this is only one of the several changes that transpired within the confines of this transition of power.

Emergence of Intersex Competition

Things continued to drastically change as technology increased in sophistication and women continued to integrate themselves into the dominance hierarchy. Beginning in the 1960s, however, something entirely new emerged: second-wave feminism wherein much of this form sought not only equality but dominance. Unlike the first wave, the several branches of the new feminist movement borrowed from the Marxist value structure that promoted an ideal of women as the dominant sex. This new ideal sought to put men and women as competitors rather than collaborators as was the case for the survival of the species in the several million years preceding this movement (Firestone, 1970; Hartmann, 1979).

The new ideal value structure evolved over the following decades to not only encompass feminism but the overarching liberal movement itself. Though many have meant well with a progressive mindset, it is essentially a left hemisphere attempt to apprehend reality, something the proponents of such claim the traditional values of conservatism do. This attempt to reorient the collective perception and mode of being has now resulted in a dichotic ideological battle.

Since the second-wave feminist movement, women as a collective have undoubtedly developed their ego, albeit in a fashion that mimics the overaccentuated orientation of their male counterpart. What happened, exactly? With modernity and its emphasis on convenience and materialism, a collective tilt towards left hemisphere dominance occurred. A narrowed and self-centered perception of reality has resulted, as is evidenced by the stark increase in narcissism over recent decades (Twenge et al., 2008). Art is no longer a means of representing the world through skill development, but rather it is a way to express oneself in an immature demonstration of will. Connection is no longer a necessity except through a technological medium that provides dopaminergic ecstasy. Cooperation is only for those who adhere to the same ideological value system as oneself — a modern manifestation of unconscious dysfunctional tribal perception.

These dysfunctional and narcissistic traits are not only found in the progressive ideals of liberalism but of traditional values of conservatism as well. Both sides are right and wrong at the same time in their analysis of the good, the bad, and the ugly. It is the left hemisphere’s narrowed perception that inhibits their contextual understanding of all the various points that articulate. Both sides analyze the parts without acknowledging the whole. Matters have only worsened as each side delves deeper — not in truth — in their ideological schematic framework. They are both equally guilty in solely assimilating information rather than accommodating and adapting.

References:

Allen, R.C. (2009). The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Cauvin, J. (2000). The Birth of the Gods and the Origins of Agriculture. Cambridge University Press.

Firestone, S. (1970). The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution. William Morrow.

Giosan, L., & Goodman, R. (2025). Morphodynamic Foundations of Sumer. PloS one, 20(8), e0329084. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0329084

Hartmann, H. (1979). The Unhappy Marriage of Marxism and Feminism: Towards a More Progressive Union. Capital & Class, 3(2), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/030981687900800102

Hobsbawm, E.J. (1969). Industry and Empire: From 1750 to the Present Day. Penguin Books.

Jung, C. (1956). Symbols of Transformation. Princeton University Press.

McGilchrist, I. (2019). The Master and His Emissary. Yale University Press.

National Research Council (2011). Explaining Divergent Levels of Longevity in High-Income Countries. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Neumann, E. (1954). The Origins and History of Consciousness. Princeton University Press.

Orwell, G. (1937). The Road to Wigan Pier. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd.

Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2020). Mortality in England and Wales: Past and projected trends in average lifespan.

Twenge, J. M., Konrath, S., Foster, J. D., Campbell, W. K., & Bushman, B. J. (2008). Egos inflating over time: a cross-temporal meta-analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. Journal of personality, 76(4), 875–928. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00507.x

Wrangham, R. (2019). The Goodness Paradox: The Strange Relationship Between Virtue and Violence in Human Evolution. Vintage.