“How increasing perceptual precision shaped human cognition, culture, and meaning.”

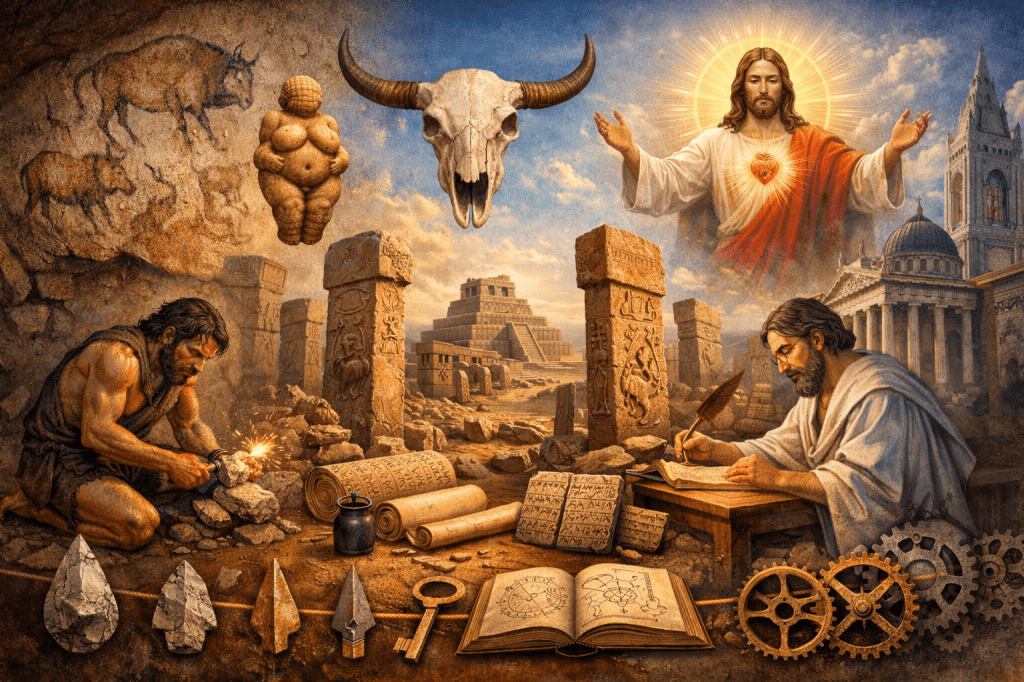

Since the emergence of Homo Sapiens onto the global scene approximately 200,000 years ago, precision in details has increased significantly. There is a variety of evidence to support this assumption, beginning with increased complexity in tool making abilities to sophisticated artistic expression to expansive narrative elaboration (Eliade, 1981; Tattersall, 2013). Each of these facets of increased precision are evident in an evolving progressive measure throughout the millennia. Among this evolving progressive trend are rapid “explosions” of creativity that occur. It is these moments that a collective elevation in conscious development appears to have taken place.

Tool making has increased in design and utility throughout both the Paleolithic and Neolithic period. Like art and architecture, tool making requires attention to details and excellent eye-hand coordination. Though this ability has been around at least since Homo habilis approximately 2.5 million years ago, it has evolved with each subsequent genus. By the time of Homo Sapiens, tool making had evolved from simple tool forms to a complex array of designs tailored for specific uses (Tattersall, 2013).

Agriculture began during the Neolithic period, and with it a variety of novel implements to help with this revolutionary means of sustenance (Cauvin, 2000). With the emergence of civilization around 5,000 years ago in both Egypt and Sumer, tool making and weapons design witnessed an incredible leap. What is most noticeable about this evolving development is precision and intricacy in design. Compared to the rudimentary forms of prehistoric times, tools at this time not only evolved in complexity, but also in substance with stones being replaced with precious metals such as copper, bronze, and iron.

Of course, this increased complexity in tool making has only accelerated since then with tools in present time not being restricted in the form of physical applications. We have now designed and built tools that are utilized in digital form to accomplish an ever-greater range of constructive and diagnostic measures. This increase can be narrowed down to an improvement in precision of perception. However, this increase may be bidirectional in that, over time of constructing and using tools, both primitive and modern humans have increasingly developed, not only an exceptional range of skills, but also increased neural activity and eye-hand coordination that has enhanced cognition (Gibson, 1991). With this enhancement came symbolic articulation.

Creative symbolic expression first appears in the form of decorative beads made of seashells over 100,000 years ago, and later these symbolic expressions expanded into deliberate etchings into rock with the oldest being approximately 77,000 years old from the Blombos caves located in southern Africa (Tattersall, 2013). Symbolic expression then took a dramatic leap in creativity following Homo Sapiens’ exodus from Africa with artwork appearing 68,000 years ago in Indonesia (Oktaviana et al., 2026). This leap in creativity resulted in a collective explosion at the beginning of the Paleolithic period approximately 50,000 years ago.

At this time, Homo Sapiens created elaborate and intricate designs featuring a variety of prehistoric animals, people, and abstract designs such as discs, wavy lines, and chevrons. Among these designs were also the first figurines that included a wealth of female designs called “Venus” figurines, and a one-off lion-man figurine (Gimbutas, 1989; Kövecses, 2023). However, these Venus figurines were ambiguous in nature, often depicting little to no facial features while possessing a “standard” obese figure, though sometimes they were also depicted in a slender manner. This ambiguity of figurines gradually developed into more elaborate articulations entering into the Neolithic era (Gimbutas, 1989; Cauvin, 2000).

In conjunction with the increased intricacy of the Venus figurines was the creation of a male counterpart that was symbolized through the bucranium, or bull’s skull. This depiction is found within the emergence of Neolithic culture around 12,000 years ago in the Middle East and later throughout Europe (Cauvin, 2000). Beginning around 7,000 years ago in Romania, a shift occurred wherein the bucranium was replaced by an actual male human figure. It was here that the Venus figurines and the new male figure sat side by side — eventually being separated into their own individual existences (Gimbutas, 1991).

During the emergence of the Neolithic period, humanity witnessed a shift in perceptual resolution and constructive ability. This shift is first evident 11,600 years ago at Gobeli Tepe located in modern-day Turkey wherein large limestone pillars stand erect in circular design. Each pillar weighs 20-50 tons while standing approximately 3.5 to 7 meters tall. These pillars exhibit carvings of various animals, symbols, and human-like features such as hands, belts, and robes (Schmidt, 2010). The elaboration of design found in the carvings and the structure itself present evidence of a sophisticated development of cognition from that found in the previous period.

As the Neolithic progressed, so too did the artistic and constructive abilities of the collective. For instance, at a site near Gobekli Tepe that is dated later at around 10,600 called Nevali Cori, there arose rectangular architecture and increased complexity of designs. It was this development in design that symbolizes a more linear, rationalistic manner of perceiving the world that had not been evident prior to. Other places throughout the Middle East like Çatalhöyük, Jericho, and Mureybet all exhibit these same rectangular architecture and intricate artwork (Cauvin, 2000; Hodder, 2007). This trend continued throughout the Neolithic period and later Bronze Age, Copper Age, and Iron Age up until modern times with increased sophistication.

With these developments of both tool making and symbolic expression came the emergence of written language. It is this revolutionary feat that provided humanity with the means of articulation that had not been available before. Prior to this time, narrative expression through the form of story telling was strictly oral which was transferred from generation to generation. However, this means of articulation has its limitations and is often less precise compared to written form. Thus, writing provided humanity with the ability to develop and articulate narratives with increased precision and coherence.

From the first written narratives of ancient Sumer and Egypt to those found centuries later in Babylon and Greece, an evolutionary trend of precision and coherence can be observed. However, regarding ancient mythology and religious ideas, the narrative found in both the Old Testament and New Testament provide the most precise and coherent formulation. It is here that humanity reached one of the most internally coherent formulations that still influences us today (Neumann, 1954). From this time, increased focus of human cognition was placed on rationalistic productions that became increasingly evident beginning at the time of the enlightenment.

The reason for this, as far as one can tell, is due to a collective psychological phenomenon. As human consciousness evolved, it developed greater precision and coherence which equates to a collective ego development. By “collective ego,” I refer not to a literal group mind, but to shared symbolic structures that increasingly differentiate subject, object, and meaning across cultures. Throughout the Paleolithic, ambiguity was a common articulation thus representing an emergence of collective unconscious symbolic representations. Over time, the collective ego developed through trial and error, contentions with climate change, and improvements in living conditions. This development became evident in the increased precision and coherence articulated through tool making, artwork, and developed ideals.

It is the latter of these that furthered its development through the narratives found throughout the ancient world. Consequently, a unification of the collective psyche resulted. This unification can be found in the latest of these highly integrated articulations — that is the person of Christ. Prior narratives of Zoroastrianism, Judaism, and Buddhism unified the various facets of the psyche that were represented in the religions of Sumer, Egypt, and Greece. However, within the Western symbolic lineage, Christianity represents one of the most psychologically coherent personifications of ego-Self integration, expressed through narrative rather than abstraction. Through the death and resurrection of the Self, one can become more precise and coherent.

This framework is presented as a psychological model of transformation rather than a theological claim. It is only by sacrificing the old perceptions through the encountered and acquisition of novel information that the process of precision and coherence can begin. From there, one wrestles with such information in efforts to create coherence in relation to one’s preconceptions. This process is not one of force as to manipulate the information to fit one’s current perceptual model, but rather a means of wrestling with one’s own Self in order to accommodate the novel information that generates increased coherence. Following this encounter and contentious experience, an individual can emerge out of the “tomb” of the unconscious in a resurrection and transformed form.

References:

Cauvin, J. (2000). The birth of the gods and the origins of agriculture. Cambridge University Press.

Eliade, M. (1981). A history of religious ideas, Volume 1: From the Stone Age to the Eleusinian Mysteries. University of Chicago Press.

Gibson, J. J. (1991). The ecological approach to visual perception. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Gimbutas, M. (1989). The language of the goddess. Harper & Row.

Gimbutas, M. (1991). The civilization of the goddess. HarperSanFrancisco.

Hodder, I. (2007). The leopard’s tale: Revealing the mysteries of Çatalhöyük. Thames & Hudson.

Kövecses, Z. (2023). Meaning-making and the mind: Conceptual metaphor theory in cultural context. Oxford University Press.

Neumann, E. (1954). The origins and history of consciousness. Princeton University Press.

Oktaviana, A. A., et al. (2026). Narrative cave art in Indonesia and the emergence of symbolic storytelling. Journal of Archaeological Science.

Schmidt, K. (2010). Göbekli Tepe – the Stone Age sanctuaries. New Results, New Interpretations. Documenta Praehistorica, 37, 239–256.

Tattersall, I. (2013). Masters of the planet: The search for our human origins. Palgrave Macmillan.