Tracing the evolution of the human psyche through the meeting of the feminine and masculine principles in the world’s first temple.

By Michael Thacker — Part III of “From Venus to Marduk: The Evolution of Sacred Consciousness” Research Series

Author’s Note: This essay continues an exploration of the evolution of consciousness through the lens of symbolic archaeology and depth psychology. Building upon The Feminine Ouroboros and The Younger Dryas and the Dawn of Consciousness, this installment examines Göbekli Tepe as the threshold between undifferentiated unity and the first emergence of dual awareness — the encounter of the First Parents.

Introduction

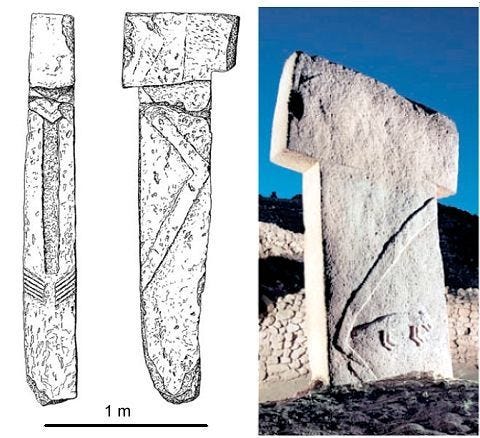

Approximately 12,000 years ago, a megalithic structure was constructed in the southern landscape of modern-day Turkey known as Göbekli Tepe (≈11,600–10,800 BP). The site consists of several circular enclosures outlined with massive T-pillars hewn from limestone, each weighing between 10 and 50 tons and standing roughly 3.5 meters tall (Judkins, 2025). The purpose of this structure remains a mystery; however, many scholars believe it served as one of the earliest temples. This is supported by a wealth of animal bones discovered at the site — indicative of ritual sacrifice (Schmidt, 2010).

Before Göbekli Tepe, humanity lived in a hunter-gatherer mode of being that required mobility and adaptability — a time known as the Paleolithic period (≈50,000–12,000 BP). Caves provided shelter and community, and within them, humanity began translating experience into abstract expression through paintings and carvings. These depictions often portray hunting scenes, likely representing either actual events or symbolic rituals (Srivastava, 2020).

Among these scenes are abstract motifs — spirals, parallel lines, and zigzags — later associated with the Divine Goddess in the Neolithic and Copper Age. This symbolic continuity, along with the widespread discovery of Venus figurines, suggests a Paleolithic emphasis on the divine feminine. The relative absence of masculine imagery outside of hunting scenes reinforces this interpretation (Gimbutas, 1989; Srivastava, 2020).

The transition from the Paleolithic to the Neolithic (≈11,800–8,500 BP) marked a profound cultural and environmental shift as hunter-gatherers began settling into agrarian life. This transition followed the Younger Dryas, a climatic reversal lasting from 12,800 to 11,500 BP that brought cold, arid conditions and resource scarcity. The subsequent return of warmth and moisture revitalized flora and fauna, catalyzing a resurgence of human creativity and the birth of agriculture (Munro, 2003).

Throughout human history, such climatic fluctuations have repeatedly triggered evolutionary leaps. For instance, the transition from Australopithecus to Homo erectus involved not only tool use, cooking, and bipedalism, but also major environmental change — a crucible that produced taller, leaner humans with doubled brain capacity (Sánchez Goñi, 2020; Wrangham, 2009).

Modern research echoes this pattern: novel environments — whether physical or informational — stimulate neuroplasticity and activate dormant genes. Studies in evolutionary epigenetics have found striking parallels between past climatic shifts and major transitions in hominid cognition (Libedinsky et al., 2025; Sánchez Goñi, 2020).

The impact of the Younger Dryas on human cognition is evident not only in the advent of agriculture but also in the construction of Göbekli Tepe. The site’s earliest phase (Layer III) immediately follows this period, ca. 11,600 BP (Dietrich et al., 2013). Its architectural sophistication, unprecedented in the archaeological record, suggests a major cognitive and cultural transformation.

Human consciousness had evolved in an exceptional way — producing the skills, imagination, and symbolic capacity to build monuments to the unseen.

Göbekli Tepe: The World’s First Temple

The precise function of Göbekli Tepe remains debated, yet most scholars agree it served as a sanctuary. Evidence of animal sacrifice and ritual feasting supports this view (Judkins, 2025; Schmidt, 2010).

Carved into its pillars are intricate symbols — animals, crescent moons, handbags, and abstract designs such as a recurring H-shaped motif. Nearby sites like Nevali Çori reveal similar architectural and ritual features, indicating a shared cultural tradition. The absence of domestic structures further reinforces the interpretation of Göbekli Tepe as a site of pilgrimage and worship (Schmidt, 2010).

Klaus Schmidt (2010), who first excavated the site, proposed that the T-pillars represent divine beings. Each pillar bears stylized arms folding above a belt, suggesting anthropomorphic figures. Schmidt and others identified them as male, citing parallels at Nevali Çori — a slightly later site whose anthropomorphic statues feature belts, robes, and loincloths. Additional evidence, such as ithyphallic statues and the “Phallic Man” of Karahan Tepe, appears to support this masculine association (Black, 2024; Verit & Verit, 2020).

However, such conclusions may be incomplete when the site is considered as a whole.

Male and Female Divinity

Viewed holistically, Göbekli Tepe and related sites evoke a more complex cosmology. The T-pillars bear striking resemblance to the so-called “stiff nudes” — columnar goddess figurines found throughout the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods. These elongated female forms, characterized by fused legs, stylized arms, and diadem-like headdresses, become especially prominent in the late Neolithic (Gimbutas, 1989; Lbova, 2021; Nishiaki et al., 2025).

The parallels between these figurines and pillars in Enclosure D are too pronounced to ignore. Since such figurines predate and postdate Göbekli Tepe, they suggest continuity in goddess symbolism rather than its replacement.

Nevali Çori provides further evidence. One totem from the site depicts a vulture atop two female figures flanked by vultures below — a clear echo of goddess and death symbology seen in both Paleolithic and Neolithic art. The female figures mirror the form of Göbekli Tepe’s pillars, complete with diadem-like crowns. Additional finds, including bird-headed human figures, recall the archetype of the bird goddess — a symbol of transformation and renewal (Schmidt, 2010).

Excavations at Nevali Çori also uncovered roughly 700 figurines, 90% of which are anthropomorphic. According to Schmidt (2010), male and female figurines appear in nearly equal number, marking an emerging balance between masculine and feminine religious representation. Given the temporal proximity of the two sites, it is plausible that Nevali Çori carried forward the ritual traditions of Göbekli Tepe.

Symbols of vultures, boars, bulls, snakes, and diadems found at Göbekli Tepe are all linked to the goddess tradition (Gimbutas, 1989; Dietrich et al., 2014). These motifs persist into the Copper and Bronze Ages, reflecting a deep continuity of sacred feminine imagery across millennia.

Göbekli Tepe thus represents not the end of matriarchal worship, but its transformation — the point where the masculine first emerges alongside the feminine, not in opposition but in complementarity. This synthesis marks the beginning of a new psychological era — the dawn of rational, structured consciousness.

The Emergence of the First Parents

The shift in consciousness embodied by Göbekli Tepe can be interpreted through a depth-psychological lens. Jung (1956) described early humanity as living in a dream-like participation with nature, immersed in the collective unconscious. As awareness evolved, symbols once lived became symbols reflected upon. Consciousness differentiated, giving rise to what Jung called the ego — the center of individuality.

This differentiation, symbolized by the mythic separation from the “first parents,” marks the beginning of self-awareness. In mythic language, the ouroboros — the eternal feminine that contains both creation and destruction — gives birth to duality. From this unity arise the first masculine and feminine forms — the primordial parents of myth (Jung, 1956; Neumann, 1954).

Within this framework, Göbekli Tepe represents the emergence of the collective ego from the collective unconscious. The circular enclosures function as symbolic wombs, while the upright T-pillars embody consciousness rising from the undifferentiated whole. Through these forms, humanity began to recognize itself — to separate subject from object, self from nature.

No longer confined to the cave walls of symbolic dream, humankind stood upright and inscribed its reflection in stone.

Conclusion

Humanity’s story is one of adaptation and awakening. Across climatic and existential thresholds, our species has repeatedly reinvented itself — not only biologically, but symbolically.

Around 50,000 years ago, Homo sapiens emerged as the sole hominid species on Earth, ushering in a creative explosion of art and myth (Srivastava, 2020). Yet it was not until the end of the Younger Dryas, nearly 12,000 years ago, that humanity achieved a new threshold — the conscious construction of meaning in stone (Munro, 2003; Schmidt, 2010).

Göbekli Tepe stands as a monument to this emergence: circular sanctuaries like wombs encasing pillars that reach skyward — the first architecture of awareness. In its synthesis of feminine and masculine symbolism, we glimpse the birth of self-reflective consciousness: the moment when humanity, for the first time, began to see itself seeing.

Closing Note:

Göbekli Tepe stands as both monument and mirror — a reflection of humanity’s earliest attempt to give shape to the ineffable mystery of being. Within its circular enclosures, consciousness began to divide and reflect upon itself — the first glimmer of the masculine and feminine as distinct yet interdependent forces.

In the next installment, I’ll explore how this differentiation gave rise to the archetypes of the Great Mother and Great Father throughout the Neolithic and Bronze Age imagination.

References:

Black, M. (2018). The Shaman Phallus. The_Shaman_Phallus.pdf

Dietrich, O., Köksal-Schmidt, Ç., Notroff, J., & Schmidt, K. (2013). Establishing a radiocarbon sequence for Göbekli Tepe — State of research and new data. Neo-Lithics, 1/13. (PDF) Establishing a Radiocarbon Sequence for Göbekli Tepe. State of Research and New Data.

Dietrich, O., Köksal-Schmidt, Ç., Kürkçüoğlu, C., Notroff, J., & Schmidt, Kl. (2014). Göbekli Tepe. Preliminary Report on the 2012 and 2013 Excavation Seasons. Neo-Lithics. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260325619_Gobekli_Tepe_Preliminary_Report_on_the_2012_and_2013_Excavation_Seasons

Gimbutas, M. (1989). The language of the goddess. Harper San Francisco.

Judkins, D. A. Göbekli Tepe in Early Civilization Development: A Reassessment of Neolithic Origins.

Jung, C. (1956). Symbols of transformation. Princeton University Press.

Lbova L. (2021). The Siberian Paleolithic site of Mal’ta: a unique source for the study of childhood archaeology. Evolutionary human sciences, 3, e9. https://doi.org/10.1017/ehs.2021.5

Libedinsky, I., Wei, Y., de Leeuw, C., Rilling, J. K., Posthuma, D., & van den Heuvel, M. P. (2025). The emergence of genetic variants linked to brain and cognitive traits in human evolution. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991), 35(8), bhaf127. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhaf127

Munro, N. D. (2003). Small game, the Younger Dryas, and the transition to agriculture in the Southern Levant. Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Urgeschichte, 12, 47–72.

Neumann, E. (1954). The origins and history of consciousness. Princeton University Press.

Nishiaki, Y., Safarova, U., Ikeyama, F., Satake, W., & Mammadov, Y. (2025). Human figurines in the Mesolithic-Neolithic transition of the South Caucasus: New evidence from the Damjili cave, Azerbaijan,

Archaeological Research in Asia, 42, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ara.2025.100611.

Sánchez Goñi, M. F. (2020). Regional impacts of climate change and its relevance to human evolution. Evolutionary Human Sciences, 2, e55. https://doi.org/10.1017/ehs.2020.56

Schmidt, K. (2010). Göbekli Tepe — the Stone Age Sanctuaries. New results of ongoing excavations with a special focus on sculptures and high reliefs. Documenta Praehistorica, 37, 239–256. https://doi.org/10.4312/dp.37.21

Verit, A., & Verit, F. F. (2021). The phallus of the greatest archeological finding of the new millenia: an untold story of Gobeklitepe dated back 12 milleniums. International journal of impotence research, 33(5), 504–507. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-020-0300-2

Wrangham, R. (2009). Catching fire: How cooking made us human. Basic Books.