Tracing the origins of human self-awareness through the symbols of fertility, death, and rebirth in Paleolithic art.

By Michael Thacker — Part I of “From Venus to Marduk: The Evolution of Sacred Consciousness” Research Series

Author’s Note: This essay marks the beginning of a four-part exploration tracing the evolution of human consciousness through its earliest symbolic expressions — from the Venus figurines of the Upper Paleolithic to the myth of Marduk and Tiamat. Each stage reflects a new step in the differentiation of the human psyche from the primordial whole.

Introduction

The mysteries of consciousness and its emergence within the human brain has captivated scholars for centuries, and yet after decades of research, little is understood about this phenomenon. From Australopithecus to Homo Erectus (≈2 million years ago), dramatic physiological and neurological anatomical changes have been observed such as taller erect bodies and larger brain size — in fact, brain size nearly doubled during this transitory period. Another leap in cognition was observed approximately 700,000–500,000 years ago with the emergences of Homo Heidelbergensis and the subsequent divergence of Homo Sapiens and Neanderthals (Libedinsky et al., 2025).

Most of these changes have been due to adaptative strategies in contending with novel environments through either migration or climate change. Adapting to these environments necessitated novel strategies such as fire use, advanced tool making and hunting methods. Recent research by Libedinsky et al. (2025) found that these adaptive strategies and their resulting innovations were due to the emergence of underlying genomic variations. Over time, these genomic variations led to increases in fluid intelligence.

Beginning approximately 40,000 years ago, intelligence in primitive humans experienced another dramatic increase (Libedinsky et al., 2025). At this time, humans began to articulate conscious thought through in a novel way — by etching symbols on cave walls and creating elaborately designed figurines. For the first time, human consciousness elevated to a level beyond simple tool making and fire building to a stage of abstraction. Symbols imbued with meaning became physically present; narratives were sketched for the eyes to behold (Aubert et al., 2019).

These symbols were not for simple entertainment purposes but were a means of communicating something that primitive humans did not understand — something deeply embedded in the collective unconscious. In this collective unconscious domain lay the necessary building blocks for the full emergence of the individual consciousness — the ego. The symbols created by these early humans were the first attempt at differentiating the ego from the collective unconscious with the earliest representation being anthropomorphic designs and Venus figurines (Neumann, 1954).

The Venus Figurines — The Feminine Ouroboros:

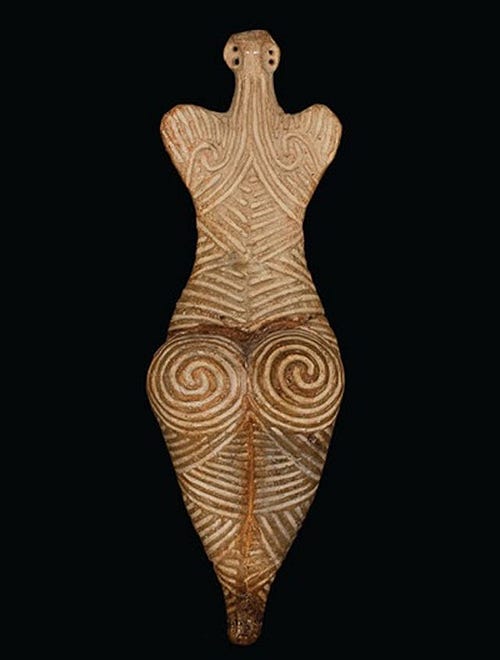

Beginning in the Upper Paleolithic (≈40,000 years ago), humans created intricately designed anthropomorphic artwork and figurines. Among these designs were the Venus figures — female depicted as either obese or pregnant (Vandewettering, 2015). Early human artists emphasized the buttocks and breasts of these figurines which symbolized the nurturance provided by the Goddess. Other distinctive features included an enlarged vagina, indicating pregnancy. After thorough investigations, Gimbutas (1991) interpreted these figurines as fertility Goddesses that were created with the intent of reverence and worship. Venuses symbolized the death and rebirth of life that was commonly observed by hunter-gatherers — a process that was later symbolized in the ouroboros. Other primitive symbols that relate to the divine feminine ouroboros include spirals, discs, and snakes. This ouroboric phase of death and rebirth represented in the Venus figurines was not merely a creative aspect of cognition, but an articulation of unconscious elements.

Through a Jungian lens, the ouroboric state was the most primitive stage of consciousness. This stage represented a full immersion in the collective unconscious wherein the individual consciousness was undifferentiated from the whole (Neumann, 1954). In parallel, Jung (1956) noted that this state of conscious awareness was akin to that of a young child who existed in the realm of dreams. Just as a child is one with the parents, so too was the primitive consciousness one with the parental essence of the tribe of which they were a part of.

At this stage of development, differentiation through the process of individuation is crucial. Individuation requires that the individual (or the collective during primitive times) acquire novel information that is often achieved through struggles that transform the individual. Transformation is equated with ego development — a differentiation from the collective (Neumann, 1954).

The first stage of individuation is symbolized through the fight with the first parents that exist within the ouroboric state. These first parents are symbolized as the feminine and masculine aspect of the ouroboros. Thus, the Venus figurines and related symbols are an encounter with the feminine aspect of the ouroboros. As humanity progressed in consciousness over the next several millennia, they encountered struggles that demanded innovative adaptive strategies to overcome. This newly acquired information helped differentiate the collective from the feminine stage of the ouroboros to the masculine — the final touchstone stage of struggle and knowledge acquisition transpiring during the Younger Dryas period (≈12,900–11,600 years ago) (Munro, 2003; Schmidt, 2010).

Closing Note:

In the next installment, I’ll explore how the circular sanctuaries of Göbekli Tepe gave rise to a new masculine principle — the first emergence of conscious order from the feminine ouroboros. You can read it here: https://michaelthacker.blog/2025/10/07/the-younger-dryas-and-the-dawn-of-consciousness-climate-crisis-and-the-rise-of-gobekli-tepe/

References

Aubert, M., Lebe, R., Oktaviana, A. A., Tang, M., Burhan, B., Hamrullah, Jusdi, A., Abdullah, Hakim, B., Zhao, J. X., Geria, I. M., Sulistyarto, P. H., Sardi, R., & Brumm, A. (2019). Earliest hunting scene in prehistoric art. Nature, 576(7787), 442–445. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1806-y

Gimbutas, M. (1991). The language of the goddess. Harper San Francisco.

Jung, C. (1956). Symbols of transformation. Princeton University Press.

Libedinsky, I., Wei, Y., de Leeuw, C., Rilling, J. K., Posthuma, D., & van den Heuvel, M. P. (2025). The emergence of genetic variants linked to brain and cognitive traits in human evolution. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991), 35(8), bhaf127. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhaf127

Munro, N. D. (2003). Small game, the Younger Dryas, and the transition to agriculture in the Southern Levant. Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Urgeschichte, 12, 47–72.

Neumann, E. (1954). The origins and history of consciousness. Princeton University Press.

Schmidt, K. (2010). Göbekli Tepe — the Stone Age Sanctuaries. New results of ongoing excavations with a special focus on sculptures and high reliefs. Documenta Praehistorica, 37, 239–256. https://doi.org/10.4312/dp.37.21

Vandewettering, Kaylea R. (2015) “Upper Paleolithic Venus figurines and interpretations of prehistoric gender representations. PURE Insights: Vol. 4 , Article 7. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/pure/vol4/iss1/7