How an Ice Age catastrophe shaped the first awakening of human consciousness and left its mark in stone at Göbekli Tepe.

By Michael Thacker — Part II of “From Venus to Marduk: The Evolution of Sacred Consciousness” Research Series

Editor’s note (Oct 2025): This essay now appears as Part II in the ongoing “From Venus to Marduk” series, following Part I on the Venus figurines and the feminine ouroboros.

Author’s Note:

This essay marks the beginning of an ongoing research series exploring the symbolic and evolutionary bridge from the Paleolithic Venus figurines to the megalithic temples of Göbekli Tepe. Each installment examines how environmental change, cognitive evolution, and mythic imagination converged to shape the dawn of civilization and the birth of human self-awareness.

Introduction

From 12,900 to 11,600 years ago, the world plunged into a deep freeze — an event called the Younger Dryas (Cheng et al., 2020). Following the end of the Last Glacial Maximum (≈14,500 BP), this event brought an abrupt shift in climate that caused global temperatures to plummet and conditions to grow markedly drier (Clark et al., . Regional fauna and plant life declined, forcing human populations to adapt through novel hunting and gathering strategies (Emra et al., 2022; Sánchez Goñi, 2020). As with earlier climatic disruptions that shaped human evolution, the Younger Dryas acted as a selection pressure that — through differentiation — helped humans ascend in consciousness (Munro, 2003; Neumann, 1954). Evidence of this ascent appears at the Neolithic site of Göbekli Tepe, which emerged directly after the Younger Dryas (Schmidt, 2010).

Younger Dryas and Adaptability

The Younger Dryas brought severe climatic instability — colder, drier conditions across much of the Levant and Europe. Before this shift, many prehistoric tribes in the Levant had begun to form stable communities during the early Natufian period (14,500 BP to 12,800 BP). Though still hunter-gatherers, these groups collected wild cereals that supported a semi-sedentary lifestyle (Munro, 2003).

The abrupt cooling reversed this progress. As regional fauna and vegetation declined, early Natufian settlements gave way to the late (12,800–11,500 BP), marked by renewed mobility and a return to foraging. Architectural remains shrink in size and number, reflecting the need for movement rather than permanence. Cultural innovation waned, and increases in secondary burials suggest the loss of stable, long-term settlements (Munro, 2003).

Psychologically, the transition mirrors the first stage of the Jungian process of individuation — when comfort gives way to struggle, and through that struggle the ego is forged. Humanity, like the individual, moved from a period of relative ease into hardship, developing a collective personality and ego through adversity. Just as ice and drought fragmented the land, they also fractured the human psyche, compelling consciousness to differentiate from its primordial (Neumann, 1954).

Adaptation and Cognitive Leap

Climate change has redirected the human evolutionary path more than once — beginning with the transitions from Australopithecus to Homo Habilis to Homo Erectus around 2 million years ago. Each leap demanded cooperation and innovation, rewarded by expanding brain capacity and cultural sophistication (Sánchez Goñi, 2020).

Likewise, the movement from late Natufian to Pre-Pottery Neolithic culture signaled a comparable cognitive surge. As the Younger Dryas ended, the climate shifted from cold and dry to warm and wet, restoring plant and animal abundance. Domestication of grains and livestock followed (Munro, 2003).

Archaeological sites such as WF16 and Jericho in the Levant reveal increasing architectural complexity and symbolic expression — clear signs of new cognitive flexibility born of the Younger Dryas crucible (Finlayson et al., 2011; Munro, 2003).

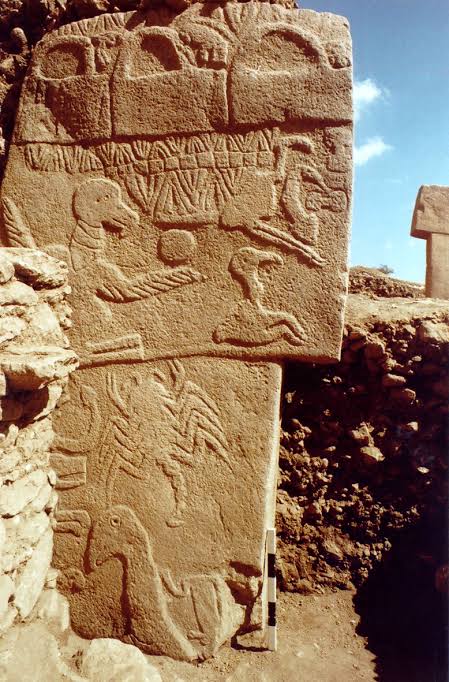

Göbekli Tepe and the Differentiation of the Collective

These innovations cultural extended northward to what is now southeastern Turkey, culminating in the megalithic wonder of Göbekli Tepe. Occupied from the 10th to the 8th millennium BCE, this site features vast circular enclosures built from T-shaped limestone pillars — some over five meters tall and weighing up to 20 tons — adorned with carvings of animal symbols, and abstract reliefs. Constructed six thousand years before Stonehenge, it stands as the earliest known monumental architecture (Schmidt, 2010).

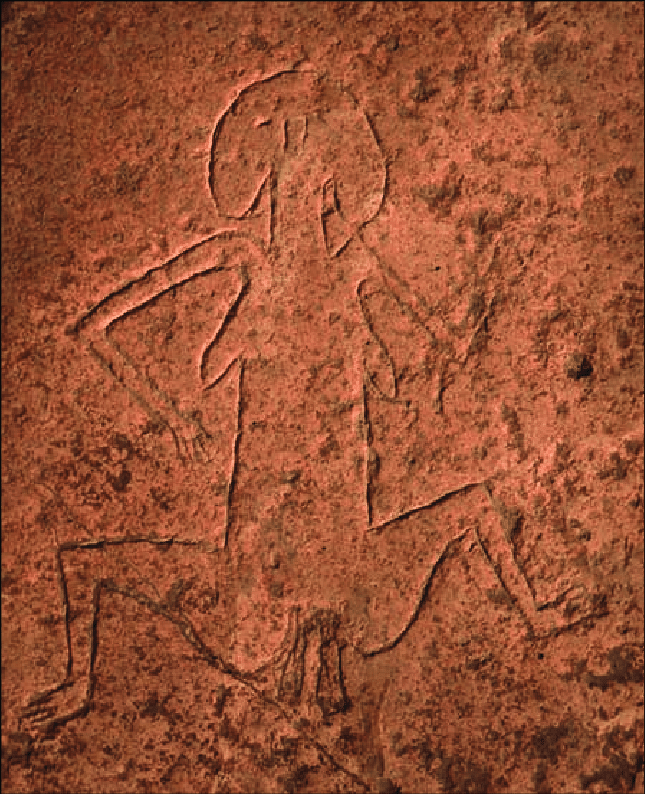

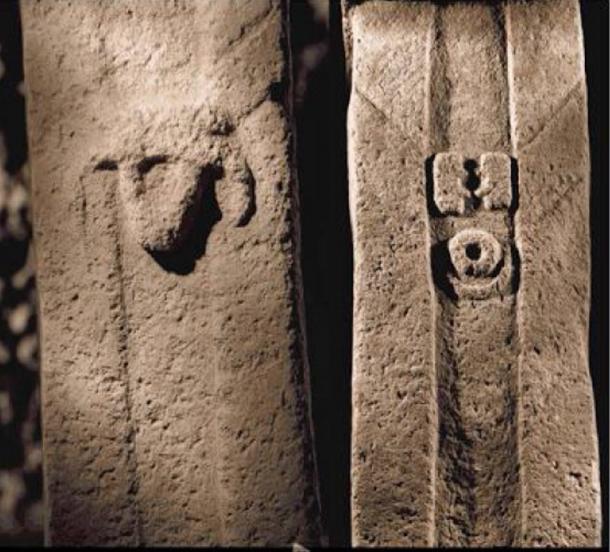

Viewed through a Jungian lens, Göbekli Tepe represents humanity’s first collective effort to impose order and meaning upon the chaos of the unconscious — the emergence of ego consciousness from the ouroboric whole. The circular enclosures may be read as an “artificial womb,” while the erect T-pillars evoke the phallic ascent of the conscious ego (Judkins, 2025). Other explicitly phallic imagery, such as the Phallic Man statue, reinforces this symbolism.

The site also encodes a dialogue between masculine and feminine forces. Boars, bulls, and solar discs carry masculine resonance; vultures, the crescent moon, and the birthing woman on Pillar 18 embody the feminine. Together they express the dual nature of the ouroboros — the tension of opposites through which consciousness is born (Judkins, 2025). Göbekli Tepe, then, can be seen as the collective ego’s first architectural gesture of differentiation.

Conclusion

Over fourteen thousand years ago, Earth’s sudden climatic upheaval forced humanity to adapt, not only physically but psychically. Through hardship, the species emerged from the complacency of the unconscious into the awakening of ego consciousness. The Younger Dryas forged a collective personality capable of perceiving order within chaos.

Göbekli Tepe embodies this breakthrough. Through traces of the ouroboros remain, the T-pillars rise as emblems of a new awareness — humanity’s first conscious architecture. From this symbolic womb of stone, the pattern spread across continents, echoing the same impulse: to lift mind from matter and shape meaning from mystery. The pillars of Göbekli Tepe mark the ascent of consciousness—but the spark that led there was already forming in the ancient figurines of the Great Mother. That is where our journey continues.

References:

Cheng, H., Zhang, H., Spötl, C., Baker, J., Sinha, A., Li, H., Bartolomé, M., Moreno, A., Kathayat, G., Zhao, J., Dong, X., Li, Y., Ning, Y., Jia, X., Zong, B., Ait Brahim, Y., Pérez-Mejías, C., Cai, Y., Novello, V. F., Cruz, F. W., … Edwards, R. L. (2020). Timing and structure of the Younger Dryas event and its underlying climate dynamics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(38), 23408–23417. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2007869117

Clark, P. U., Dyke, A. S., Shakun, J. D., Carlson, A. E., Clark, J., Wohlfarth, B., Mitrovica, J. X., Hostetler, S. W., & McCabe, A. M. (2009). The Last Glacial Maximum. Science (New York, N.Y.), 325(5941), 710–714. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1172873

Emra, S., Benz, M., Siddiq, A. B., & Özkaya, V. (2022). Adaptions in subsistence strategy to environment changes across the Younger Dryas — Early Holocene boundary at Körtiktepe, Southeastern Turkey. The Holocene, 32(5), 390–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/09596836221074030

Finlayson, B., Mithen, S. J., Najjar, M., Smith, S., Maričević, D., Pankhurst, N., & Yeomans, L. (2011). Architecture, sedentism, and social complexity at Pre-Pottery Neolithic A WF16, Southern Jordan. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(20), 8183–8188. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1017642108

Judkins, D. A. Göbekli Tepe in Early Civilization Development: A Reassessment of Neolithic Origins.

Munro, N. D. (2003). Small game, the Younger Dryas, and the transition to agriculture in the Southern Levant. Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Urgeschichte, 12, 47–72.

Neumann, E. (1954). The origins and history of consciousness. Princeton University Press.

Sánchez Goñi, M. F. (2020). Regional impacts of climate change and its relevance to human evolution. Evolutionary Human Sciences, 2, e55. https://doi.org/10.1017/ehs.2020.56

Schmidt, K. (2010). Göbekli Tepe — the Stone Age Sanctuaries. New results of ongoing excavations with a special focus on sculptures and high reliefs. Documenta Praehistorica, 37, 239–256. https://doi.org/10.4312/dp.37.21