From the African savanna to modern society, humanity’s story is one of balance. By tracing natural selection, sexual selection, and Jung’s anima and animus, we uncover the deeper roots of adaptability and individuation.

Natural Selection

Six million years have passed since chimpanzees and humans last shared a common ancestor (Almécija et al., 2021). Since that time, chimpanzees have experienced little evolutionary change, while humans have developed into sophisticated beings capable of constructing megalithic structures and solving complex problems (Wilson, 2021). Why this divergence? Divine intervention? Perhaps. Yet the more likely driver was adaptability to novel environments—that is, natural selection. Humans emerged from the African forest to engage with the broader world, while our counterparts remained in the relative safety of the trees (Han, 2015).

Still, the evolutionary story is more complex. Natural selection equipped humans with useful and increasingly complex skills—bipedalism, hunting, cooking, and toolmaking. These skills supported the growth of larger brains and more mobile bodies, enabling early hominids to think and act in increasingly sophisticated ways (Han, 2015; Wrangham, 2010). Communication improved, as did the ability to grasp others’ thoughts and feelings—primitive forms of empathy were emerging (Spikins, 2022; Wrangham, 2019). Gradually, culture developed, built from shared beliefs and ideas rooted in collective experience, thought, and feeling (Mesoudi, 2016).

Sexual Selection

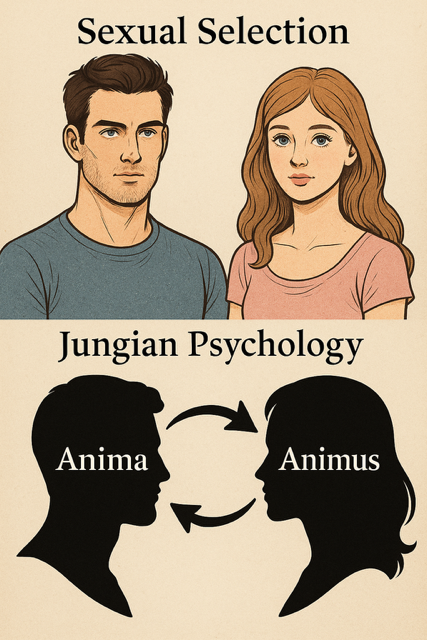

Interwoven with natural selection and cultural development was sexual selection. Darwin defined it as “the advantage which certain individuals have over other individuals of the same sex and species solely in respect of reproduction” (Hoskin & House, 2011, p. 62). In simpler terms, sexual selection is the competition for status and attractiveness that leads to successful mating.

Throughout human prehistory, males competed with each other to gain access to desirable females, and females likewise competed for high-quality males. Attractive qualities in both sexes generally signaled health and fertility. For males, broad shoulders, muscular build, pronounced jawline, and symmetrical features were not merely aesthetic but markers of vitality. For females, symmetry also mattered, but so did traits such as a favorable hip-to-waist ratio, petite frame, and neotenous facial features. In both sexes, all these features are shaped by hormonal influences (Wilson et al., 2017).

These complementary sexes provided balance in survival. Their distinct roles extended beyond reproduction into daily life: men often hunted large game, while women gathered nearby foods and nurtured their young. Such role differentiation remains visible in modern hunter-gatherer groups like the African !Kung (Wrangham & Peterson, 1997).

Adaptability

Although distinct gender roles created functional societies, Wrangham (2019) observed that individuals who could integrate both sets of qualities tended to fare better. What does this mean? Men who could embody masculine features in contexts such as war and hunting, yet also show nurturance and empathy, were especially valued by females. Likewise, women who could be both nurturing and resilient were more likely to thrive.

This dual adaptability is both evolutionary and psychological. Jung later conceptualized this process in terms of the anima and animus—the integration of opposite qualities within the self (Saiz & Grez, 2022).

Integration of the Anima and Animus

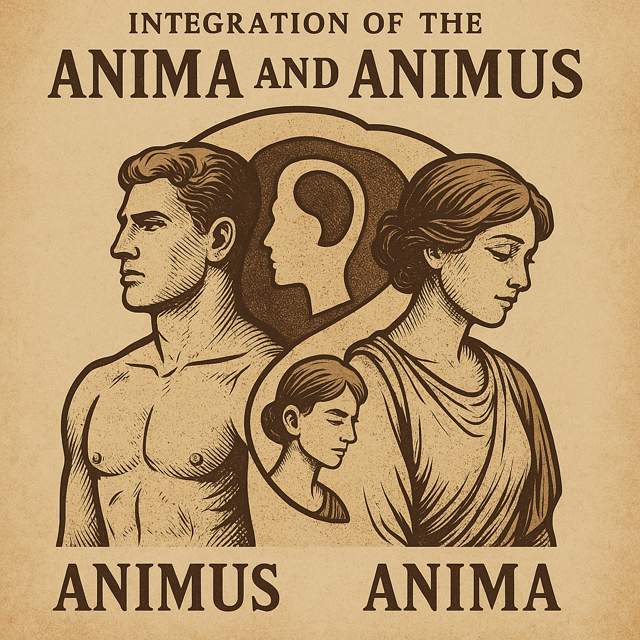

The anima–animus dynamic lies at the heart of individuation—the process by which unconscious elements are integrated into the ego. Individuation requires engaging with both one’s inner world and outside environment. Through this work, individuals gradually become whole, weaving both negative and positive aspects of the personal and collective unconscious into their conscious self. For men, this means integrating the feminine anima;—for women, the masculine animus (Saiz & Grez, 2022).

Progressing through this integration fosters a balanced, adaptable perception of reality rooted in both empathy and strength. Men gain greater emotional understanding, enhancing their capacity for nurturance and compassion—qualities invaluable in parenting or supporting loved ones. Women, in turn, develop increased resilience and assertiveness, assets in professional settings or ambiguous, high-pressure situations.

Importantly, this integration does not suggest that men should become women or vice versa. Rather, it is the pursuit of balance—the ability to draw on both masculine and feminine qualities as situations demand. Biological sex is the orienting foundation, while integration of the anima and animus enhances psychological adaptability. Together, balance and adaptability guide the journey toward a holistic mode of being. Each step of integration moves the individual closer to wholeness—a union of mind and body that fosters both strength and wisdom, both animus and anima. Thus, individuation is not a luxury of the modern psyche, but an evolutionary necessity—our deepest inheritance for survival and wholeness.

References:

Almécija, S., Hammond, A. S., Thompson, N. E., Pugh, K. D., Moyà-Solà, S., & Alba, D. M. (2021). Fossil apes and human evolution. Science (New York, N.Y.), 372(6542), eabb4363. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb4363

Han, G. (2015). Origins of bipedalism. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology. DOI:10.13140/RG.2.1.5092.4647

Hosken, D. J., & House, C. M. (2011). Sexual selection. Current biology: CB, 21(2), R62–R65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2010.11.053

Mesoudi, A. (2016). Cultural evolution: integrating psychology, evolution and culture. Current Opinion in Psychology, 7, 17–22, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.07.001.

Saiz, M. E., & Grez, C. (2022). Inner-outer couple: anima and animus revisited. New perspectives for a clinical approach in transition. The Journal of analytical psychology, 67(2), 685–700. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5922.12789

Spikins, P. (2022). The evolutionary basis for human empathy, compassion and generosity. York: White Rose University Press. https://doi.org/10.22599/HiddenDepths.b

Wilson M. L. (2021). Insights into human evolution from 60 years of research on chimpanzees at Gombe. Evolutionary human sciences, 3, e8. https://doi.org/10.1017/ehs.2021.2

Wilson, M. L., Miller, C. M., & Crouse, K. N. (2017). Humans as a model species for sexual selection research. Proceedings. Biological sciences, 284(1866), 20171320. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.1320

Wrangham, R. (2010). Catching fire: How cooking made us human. Basic Books.

Wrangham, R. (2019). The goodness paradox: The strange relationship between virtue and violence in human evolution. Vintage Publishing.

Wrangham, R & Peterson, D. (1997). Demonic male: Apes and the origins of human violence. Mariner Books.