Series Note:

This is the first installment in a two-part research series on the effects of modernity on the mental health of young adult men. Part One investigates the problem of rising depression among young men through evolutionary and Jungian analysis. Part Two will build on this foundation by outlining an integrative treatment approach that combines biological reconnection with psychological meaning-making.

Abstract

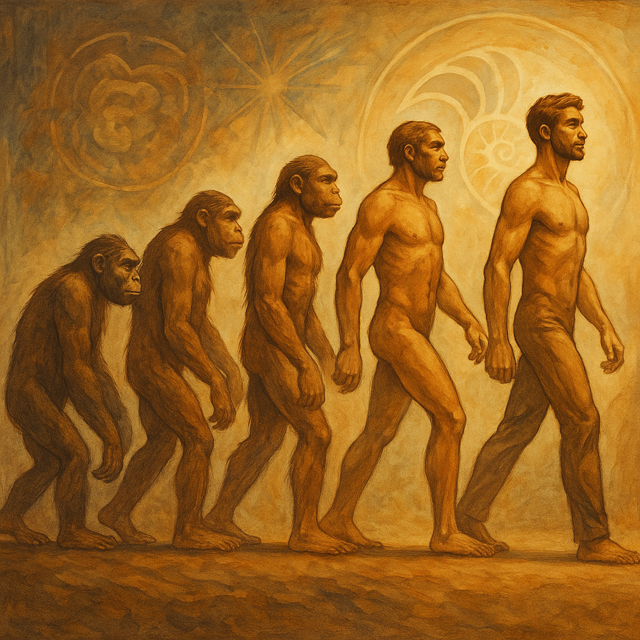

Depression among young adult males in the United States has increased substantially in recent decades, now representing the highest prevalence of depression of any male age group. While commonly attributed to factors such as the Covid-19 pandemic, stress, obesity, and social media use, these explanations remain incomplete. This paper integrates evolutionary psychology and Jungian theory to analyze the deeper substrates of this phenomenon. From an evolutionary perspective, rapid brain expansion, heightened sensory sensitivity, and rising intelligence have increased susceptibility to depression, while modernization and technology have intensified overstimulation, social disconnection, and sedentary lifestyles. Jungian psychology complements this framework by framing depression as a symbolic crisis of meaning, rooted in a loss of transcendent orientation and failure to integrate unconscious elements of the self. Together, these perspectives reveal depression not merely as disorder but as both a mismatch between biology and environment and a cultural-psychological crisis of meaning. Such a dual-lens approach clarifies the nature of the problem and points toward solutions that address both body and psyche.

Keywords: depression; young men; evolutionary psychology; Jungian theory; young adults; depth psychology; mental health

Depression rates among young adults (ages 18-30) in the United States have increased substantially over the past two decades (Kranjac et al., 2025). This age group now reports the highest prevalence of depression at 21%, surpassing all other age groups (Villarroel & Terlizzi, 2020). While the differences between males (14.3%) and females (19%) are relatively similar (Brody & Hughes, 2025), the consequences tend to be more severe for males, who die by suicide 3.6 times higher than females (Sileo & Kershaw, 2020). Men int this age range often experience distinctive symptom patterns that involve anger, aggression, risk-taking, and substance abuse (Sileo & Kershaw, 2020). Recent statistics have revealed that young adult males have the highest depression rates of all male age groups (Brody & Hughes, 2025). This growing burden not only undermines their well-being but also reverberates through families, communities, and society as a whole (Kranjac et al., 2025).

Furthermore, an increase in depression also corresponds with increased societal and economic burdens. For example, research has demonstrated that increases in depression among the general population have been linked to a 37.9% increase in economic burden, equating to an estimated $100 billion deficit in the U.S. alone (Greenberg et al., 2021). Globally, mental health costs are projected to reach $6 trillion, with depression being the leading contributor. Beyond economics, depression disrupts every domain of functioning–social life, physical health, intimate relationships, parenting and performance in both school and work (Kupferberg & Hasler, 2023). If current trajectories persist, the outcome could be a bleak future. Addressing this challenge requires identifying the deeper underlying factors while ensuring treatment options are effective and widely accessible.

Scholars have advanced numerous explanations for the increasing rates of depression among young adult males. Historical factors include the Covid-19 pandemic, rapid technological modernization, and the pervasive influence of social media have played notable roles (Kranjac et al., 2025). Biological factors, including increased obesity (Blasco et al., 2020) and greater consumption of processed foods (Limbana et al., 2020), have also been implicated. Additionally, researchers argue that the accelerating pace of modern life that necessitates multitasking, has exacerbated stress and emotional strain (Zehra et al., 2025).

While these explanations hold validity, they represent only pieces of a broader framework. A comprehensive understanding must integrate these diverse factors to more fully explain the complex rise in depression among young men. Examining these dynamics through the dual lenses of evolutionary psychology and Jungian theory provides deeper insight into the fundamental substrates of this phenomenon. Such a framework not only clarifies the issue but also lays the groundwork for more effective solutions.

Theoretical Application

Both evolutionary psychology and Jungian theory operate within the realm of the fundamental substrates of human experience. A productive analysis through these lenses involves first dissecting the underlying substrates and then tracing their emergence toward unification. Evolutionary psychology accomplishes this through an evolutionary framework with a strong biological foundation. An issue of consideration within this framework is the potential neglect of cultural nuances. In contrast, Jungian theory engages the deeper interplay of the unconscious and conscious self. This framework emphasizes individuation and meaning; however, it possesses less empirical validation compared to evolutionary psychology. Though these differences are distinct, ultimately, these frameworks complement each other. Evolutionary psychology fills in the gaps of empirical validity while Jungian theory provides cultural comprehension.

Evolutionary psychology

Evolutionary psychology is founded on the premise that, alongside biological adaptation, psychological traits also underwent evolutionary processes of change. Psychological adaptiveness refers to behavioral and cognitive shifts that increase survival and social cohesion (Han & Chen, 2020). Moreover, adaptiveness encompasses the evolution of consciousness and intelligence (Kanaev, 2022). Unlike other species, humans have been able to adjust behavior to fit increasingly complex social environments. This complexity necessitates higher levels of self-awareness (consciousness) and intelligence in order to assimilate novel information. As new information is assimilated, humans transform their perceptual frameworks (schemas) resulting in behavioral changes. Over time, these changes fostered cooperation and relationship structures that ensured group survival (Kanaev, 2022).

However, with greater social complexities and higher consciousness comes increased susceptibility to mental illness. Heightened sensory sensitivity, linked to the development of the frontal lobe, plays a major role in this vulnerability (Galecki & Talarowska, 2017; Greven et al., 2019). Since the emergence of the Homo genus 2.5 million years ago, the human brain has undergone rapid expansion. Cortical developments were driven by multiple interactive processes, including bipedalism, social cohesion, tool making, and cooking (Galecki & Talarowska, 2017; Heyes, 2012; Wrangham, 2009).

These periods of expansion produced a brain with vastly increased neural circuitry, particularly in the cerebral cortex–the outer layer associated with advanced intelligence and sense of self (Parks & Smaers, 2018). Within the frontal lobe especially, humans developed capacities for critical thinking, emotional regulation, and abstract reasoning. Yet, as these capacities grew more refined, they also became more vulnerable to environmental stressors (Galecki & Talarowska, 2017).

This vulnerability is best understood through the concept of overexcitabilities, developed by Polish psychiatrist Kazimierz Dabrowskiof. Overexcitabilities, closely linked to higher intelligence, occur across five domains: emotional, intellectual, sensory, psychomotor, and imaginational domains. Individuals with such traits experience the world with hyper-reactivity, processing stimuli more deeply in ways that “overexcite” the central nervous system, leading to heightened risk for conditions such as depression (Karpinski et al., 2018). As the frontal lobe developed and average IQ levels rose (Pietschnig & Voracek, 2015), susceptibility to mental illness likewise increased (Galecki & Talarowska, 2017).

Modernization and technological advancement have exacerbated this trend (Hidaka, 2013). Within higher-IQ populations, overexcitabilities are especially pronounced (Karpinski et al., 2018). Consequently, susceptibility to depression has intensified, particularly among younger generations that have matured within highly technological and socially accelerated environments (Small et al., 2020).

Jungian psychology

A derivative of psychoanalytic theory developed by Carl Jung (1875-1961), Jungian psychology emphasizes depth psychology such as the ego, collective unconscious, archetypes, individuation, dream analysis, and alchemical symbolism (Vibhute & Kumar, 2024). Jung argued that the onset of psychological disorders often stemmed from a loss of meaning. He believed modernity intensified this loss, particularly through the decline in religious belief–a trend foreshadowed in Friedrich Nietzsche’s proclamation of the “Death of God.” With this decline in transcendent meaning, Jung suggested that individuals and societies would require new sources of meaning to restore psychological balance (Roesler & Reefschläger, 2021).

Recent data underscores Jung’s concerns. A Gallup poll revealed that only 81% of Americans say they believe in God–an all-time low, down from 87% in 2017 and dramatically lower than the 98% reported in the mid-20th century. Among young adults, belief dropped to just 68% (Jones, 2022). Similarly, a 2023 report from Harvard University released in 2023 found that 58% of U.S. young adults reported lacking meaning or purpose in the past month (Making Caring Common, 2023). The parallel decline rise of depression alongside this decline in meaning provides contemporary support Jung’s hypothesis.

Modernity’s impact on meaning is further evident through globalization. As internet access expands, alternative ideas increasingly disrupt local traditions. While encountering novel perspectives can be enriching, the overwhelming influx of information often produces cultural upheaval. Psychologically, assimilating such volumes of data coherently is difficult, leading to societal, cultural, and individual distress (Angkasawati, 2024). For Jung, the path forward lies in rediscovering meaning–individually and collectively–through the process of individuation (Roesler & Reefschläger, 2021).

Existing Research

From early hominins sharing a common ancestor with chimpanzees six million years ago to the rise of agriculture 12,000 years ago, humans evolved within and alongside nature (Carey, 2023; Young et al., 2015). Nature was essential not only for survival but also for cultural development (Rigolot, 2021). Through fire-making, cooperative hunting, communal cooking, early humans forged shared customs and value systems. These cooperative frameworks fostered meaning, adaptive coping strategies, and a collective sense of fulfillment (Kanaev, 2022).

Since the Industrial Revolution, however, urban migration and rapid technological advancement have shifted priorities toward convenience and consumerism. While progress itself is not inherently problematic, the pace of change has often disrupted transcendent orientations, contributing to the rise in depression (Alsaleh, 2024; Groumpos, 2021).

Cross-cultural evidence illustrates this disruption. For instance, Ik of Uganda, depression and suicide rates rose sharply after their transition into modernity (Steven & Price, 2000). A broader comparative study of hunter-gatherer tribes similarly found that depression prevalence increased post-transition, with outcomes linked to the speed of modernization: gradual exposure lessened the effect, while rapid exposure amplified it (Colla et al., 2006).

The same dynamic appears in urbanized societies. For example, a recent meta-analysis of 80 studies with over 500,000 participants found higher depression rates in urban environments compared to rural ones–particularly in developed nations, where the gap between rural and urban life is stark (Xu et al. 2023). Neuroimaging research also shows urban living’s toll: high levels of stress and pollution in urban areas negatively affect the mPFC in developing brains, a region strongly tied to depression risk. However, the demographic used in this study was European and Chinese populations, and therefore the generalizability might be limited (Jiayuan et al., 2022).

Globalization via internet access also disrupts cultural cohesion. Though exposure to diverse ideas can enrich individuals and communities, rapid, unfiltered influxes often produce identity gaps and psychological strain (Alsaleh, 2024; Angkasawati, 2024). One study involving 171 international students found a significant correlation of p<0.001 between acculturative stress, identity gaps, and depression (Amado et al., 2020). This suggests that young people navigating globalized digital spaces may experience similar challenges.

On a microscale, modernization contributes to depression through physiological and lifestyle changes. These include disruptions to the gut microbiome, obesity, and declining testosterone in young men (Blasco et al., 2020; Hauger et al., 2022; Lambana et al., 2020). Technology compounds the issue, with devices linked to reduced attention, social isolation, impaired social-emotional intelligence, and addiction (Small et al., 2020). Emerging research even warns of neurological impacts: MIT study reported reduced frontal lobe connectivity in young adults who frequently rely on large-language models (Kosmyna et al., 2025), echoing earlier findings that reduced frontal activity correlates with depression (Dai et al., 2019).

Collectively, this research highlights a growing incompatibility between modernity and young men’s evolved mode of being. The excess reliance on technology resulting in sedentary lifestyles fosters an imbalance between past adaptations and present environmental requirements. Where young men were once valued as hunters and warriors who thrived through physical challenges and communal bonds, today they face overstimulation, sedentary lifestyles, weakened social cohesion, and eroded value structures–all of which contribute to rising depression.

Cultural Considerations

Jarrod E. Bock and colleagues (2025) highlight that the U.S. retains strong elements of honor culture, which is positively associated with depression. Central to this cultural framework is the defense of reputation, with men expected to be strong, brave, and ready to confront threats. Within such a system, perceived weakness has little tolerance. When young men experience vulnerability, they often conceal it, fearing criticism from peers or family. This stigmatization not only worsens depressive symptoms but also discourages help-seeking behaviors (Bock et al., 2025).

Another consideration is the predominance of Western and predominantly white samples in some of the studies cited, and in Jungian theory itself. Many investigations, especially those using university cohorts, were composed largely of white or Asian participants, limiting cultural generalizability (Kosmyna et al., 2025; Xu et al., 2022). Similarly, Jungian theory, rooted in European traditions, may not fully capture the psychosocial dynamics of other cultural groups (Vibhute & Kumar, 2024). Nonetheless, several studies did incorporate more diverse samples (Amado et al., 2020; Angkasawati, 2024; Xu et al., 2023), and evolutionary psychology remains broadly applicable humanity as a whole.

Ethical Considerations

Two APA (2017) ethical principles are especially relevant here: integrity and justice. Integrity requires psychologists to present information accurately and avoid misrepresentation. While limited deception may be used in experiments, researchers must carefully weigh potential consequences. In interpreting findings, scholars should minimize ideological bias to preserve accuracy and transparency.

Justice emphasizes equal access to benefits of psychological research and practice. Psychologists must evaluate their own biases and expertise to avoid perpetuating inequities. For instance, when working with young adult men, practitioners should take care to recognize male-specific needs and ensure treatment is both adequate and contextually relevant (APA, 2017).

Conclusion

Depression rates have risen sharply in recent years, with consequences that extend far beyond the individual to the broader fabric of society (Kranjac et al., 2025). Young men, in particular, have been disproportionately affected, exhibiting significantly higher suicide rates than women (Sileo & Kershaw, 2020). Among men, those in this age group report the highest prevalence of depression (Brody & Hughes, 2025). If this trend persists, the long-term social and economic repercussions will be severe (Kupferberg & Hasler, 2023), with recent research estimating the economic burden of depression in the U.S. at $100 billion (Greenberg et al., 2021).

The underlying causes are complex. Scholars often emphasize factors such as Covid-19, obesity, stress, and modernity, but these remain only part of the broader framework (Alsaleh, 2024; Blasco et al., 2020; Lambana et al., 2020; Xu et al. 2023). Increased IQ levels and heightened sensory sensitivity, compounded by rapid technological advancements, have disrupted and overwhelmed the natural adaptive state of young men (Karpinski et al., 2018; Pietschnig & Voracek, 2015). Urbanization and sedentary lifestyles have further intensified the challenge (Xu et al. 2023). From an evolutionary psychology perspective, these patterns reflect the inability of natural selection to keep pace with the accelerated demands of modernity (Han & Chen, 2020; Kanaev, 2022). Similarly, Jungian theory offers a depth-psychological analysis, highlighting the role of the unconscious and collective meaning in shaping both the problem and potential solutions (Roesler & Reefschläger, 2021; Vibhute & Kumar, 2024).

Together, evolutionary psychology and Jungian theory provide complementary frameworks for both diagnosis and solutions. Yet, when considering potential solutions, both cultural factors and ethical principles must be considered. Scholars must account for cultural variation in both the origins and treatment of depression, while adhering to ethical principles of integrity and justice to ensure accuracy of interpretation and equal access to interventions (APA, 2017). Ultimately, the goal is not simply to alleviate depressive symptoms in a subset of young men but to design approaches that reach across diverse populations. Solutions must also be framed in ways that encourage young men to seek help without fear of stigma, thereby fostering resilience at both the individual and societal level.

References

Alsaleh, A. The impact of technological advancement on culture and society. Science Report, 14, 32140 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83995-z

Amado, S., Snyder, H. R., & Gutchess, A. (2020). Mind the gap: The relation between identity gaps and depression symptoms in cultural adaptation. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 1156. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01156

American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. https://www.apa.org/ethics/code

Angkasawati, A. (2024). The impact of modernization on social and cultural values: A basic social and cultural sciences review. International Journal of Education, Vocational and Social Science, 3, 56-65. DOI:10.63922/ijevss.v3i04.1228

Blasco, B. V., García-Jiménez, J., Bodoano, I., & Gutiérrez-Rojas, L. (2020). Obesity and depression: Its prevalence and influence as a prognostic factor: A systematic review. Psychiatry investigation, 17(8), 715–724. https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2020.0099

Bock, J. E., Brown, R. P., Johns, N. E., Closson, K., Cunningham, M., Foster, S., & Raj, A. (2025). Is honor culture linked with depression?: Examining the replicability and robustness of a disputed association at the state and individual levels. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/00220221251348586

Brody DJ, Hughes JP. Depression prevalence in adolescents and adults: United States, August 2021–August 2023. 2025 Apr; NCHS (527)1–11. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc/174579

Dai, L., Zhou, H., Xu, X., & Zuo, Z. (2019). Brain structural and functional changes in patients with major depressive disorder: a literature review. PeerJ, 7, e8170. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.8170

Gałecki, P., & Talarowska, M. (2017). The evolutionary theory of depression. Medical science monitor:international medical journal of experimental and clinical research, 23, 2267–2274. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.901240

Greenberg, P. E., Fournier, A. A., Sisitsky, T., Simes, M., Berman, R., Koenigsberg, S. H., & Kessler, R. C. (2021). The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2010 and 2018). PharmacoEconomics, 39(6), 653–665. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-021-01019-4

Groumpos, P. P. (2021). A critical historical and scientific overview of all industrial revolutions. IFAC-PapersOnLine, 54, 464-471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifacol.2021.10.492

Han, W., & Chen, B. B. (2020). An evolutionary life history approach to understanding mental health. General psychiatry, 33(6), e100113. https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2019-100113

Hidaka B. H. (2012). Depression as a disease of modernity: Explanations for increasing prevalence. Journal of affective disorders, 140(3), 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.036

Jiayuan, X., Liu, X., Li, Q., Ran, G., Wen, Q., Liu, F., Congying, C., Qiang, L., Ing, A., Lining, G., Liu, N., Huaigui, L., Conghong, H., Jingliang, C., Wang, M., Zuojun, G., Zhu, W., Zhang, B., Weihua, L., . . . Gunter, S. (2022). Global urbanicity is associated with brain and behaviour in young people. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(2), 279-293. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01204-7

Jones, J.M. (2022). Belief in God in U.S. dips to 81%, a new low. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/393737/belief-god-dips-new-low.aspx

Kanaev, I.A. (2022). Evolutionary origin and the development of consciousness, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 133, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.12.034

Karpinski, R.I., Kolb, A.M.K., Tetreault, N.A., & Borowski, T.B. (2018). High intelligence: A risk factor for psychological and physiological overexcitabilities, Intelligence, 66, 8-23, ISSN 0160-2896, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2017.09.001.

Kosmyna, N., Hauptmann, E., Yuan, Y.T., Situ, J., Liao, X-H., Beresnitzky, V.A. Braunstein, I. & Maes, P. (2025). Your brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of cognitive debt when using an AI assistant for essay writing tasks. MIT. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2506.08872

Kranjac, A.W., Kranjac, D. & Chung, V. (2025). Temporal and generational changes in depression among young American adults. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 21, 100949, ISSN 2666-9153, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2025.100949.

Kupferberg, A. & Hasler, G. (2023). The social cost of depression: Investigating the impact of impaired social emotion regulation, social cognition, and interpersonal behavior on social functioning. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 14, 100631, ISSN 2666-9153, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2023.100631.

Limbana, T., Khan, F., & Eskander, N. (2020). Gut microbiome and depression: How microbes affect the way we think. Cureus, 12(8), e9966. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.9966

Making Caring Common. (2023). On edge: Understanding and preventing young adults’ mental health challenges. https://mcc.gse.harvard.edu/reports/on-edge

Parks, A.N., Smaers, J.B. (2018). The evolution of the frontal lobe in humans. In: Bruner, E., Ogihara, N., Tanabe, H. (eds) Digital endocasts. replacement of neanderthals by modern humans series. Springer, Tokyo. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-56582-6_14

Pietschnig, J., & Voracek, M. (2015). One century of global IQ gains: A formal meta-analysis of the Flynn effect (1909-2013). Perspectives on psychological science: a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 10(3), 282–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615577701

Rigolot C. (2021). Our mysterious future: Opening up the perspectives on the evolution of human-nature relationships. Ambio, 50(9), 1757–1759. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-021-01585-z

Roesler, C., & Reefschläger, G. I. (2022). Jungian psychotherapy, spirituality, and synchronicity: Theory, applications, and evidence base. Psychotherapy, 59(3), 339–350. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000402

Small, G. W., Lee, J., Kaufman, A., Jalil, J., Siddarth, P., Gaddipati, H., Moody, T. D., & Bookheimer, S. Y. (2020). Brain health consequences of digital technology use. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 22(2), 179–187. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2020.22.2/gsmall

Vibhute, S. & Suresh, K. (2024). Unraveling the depths of the psyche: A review of Carl Jung’s analytical psychology. International Journal of Indian Psychology. 12. 628-642. DOI:10.25215/1201.059

Xu, C., Miao, L., Turner, D., & DeRubeis, R. (2023). Urbanicity and depression: A global meta-analysis. Journal of affective disorders, 340, 299–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.08.030

Young, N. M., Capellini, T. D., Roach, N. T., & Alemseged, Z. (2015). Fossil hominin shoulders support an African ape-like last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(38), 11829–11834. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1511220112