Introduction

Since the time humans branched off from chimpanzees approximately six million years ago, humans have evolved into a larger and more complex species through influencing factors such as bipedalism, tool crafting, cooking, climate change, socialization, and pair bonding (Wrangham, 2009; Tuttle, 2024; Timmermann et al., 2024). The latter of these factors was initially accomplished through the evolutionary process of sexual selection, and with it a greater parental investment from both males and females that required greater cooperation between the sexes, as well as helped contribute to the formation of human culture (Larsen, 2023). The process of sexual selection is predominately accomplished through the selectivity of females in their choice of male mating partners that has helped shape variations between human female and male brains throughout the past two million years or so. This process has impacted males and females in different ways that have contributed to neuroanatomical and physiological differences between the sexes (Stanyon & Bigoni, 2014).

Although sexual selection has been one of the guiding forces that have helped human evolution through a pathway that has brought about changes both physiologically and neuroanatomically that helps distinguish between male and females, it is still only the tip of the iceberg of causal factors of anatomical differences between the sexes. However, even with acknowledged differences with some that have recently been disclosed that will be discussed shortly, there are still plenty of opponents to these differences that believe there to be no outstanding differences between male and female brains at all with most differences being solely a byproduct of immediate environmental and social influences. To help address this conundrum between perspectives, this paper will first examine the field of biology in a comparative and contrasting approach to the study of sex differentiation, followed a brief overview of a flawed source claiming such a concept. From there, evidence found within recent studies will be assessed as well as a psychological theory pertaining to sex differentiation.

Biology of Sex Differences

Biology is the study of a living species and their vital processes with focuses on underlying processes such as genetics, hormones, cellular and immune function, among others Britannica, 2021). Although biology focuses on the physiological components of humans while the field of psychology studies the functionality of the mind, the two fields of study complement each other. With the help from biology, psychologists can better understand the underlying biological markers that help drive behavior, which is a crucial factor in understanding the psychological processes and the overall functionality of any species. Vice versa, psychology can help biologists discover root causes of certain behaviors that have been analyzed by psychologists as their work helps provide cues as to what might be underlying the behavior of interest (Garrett & Hough, 2022).

Biology has helped shed light on the underlying biological functions that help differentiate males and females while psychology has helped compliment this information through the perceptual and behavioral differences between the sexes. For instance, males produce 15 to 20 times more testosterone than females which is linked to greater muscle mass, increased aggression and sexual drive, decreased sensitivity to stress, and risky behavior. Testosterone is also a vital hormone in the development of male sexual hormones during gestation that is accomplished by stimulating the development of the Wolffian ducts that results in male external genitalia (Garrett & Hough, 2022). This data on testosterone not only helps explain some of the biological differences between males and females, but it also helps understand neurological and perceptual differences between the sexes as well (Zitzmann, 2020).

Flawed Source

According to Elle Beau, a user on Medium, there are minor differences between male and female brains. The only evidence to support her claim was that most studies revealing differences between male and female brains were insignificant findings as well as flawed in their design with small sample sizes. She also states that the only genuine difference between the brains is the portion of the brain that enervates the male penis (2024).

Peer-Reviewed Sources

Three recent studies will be examined here to help rebuttal the flawed source as well as help further enhance the complexity of the human brain regarding gender differentiation.

Source 1

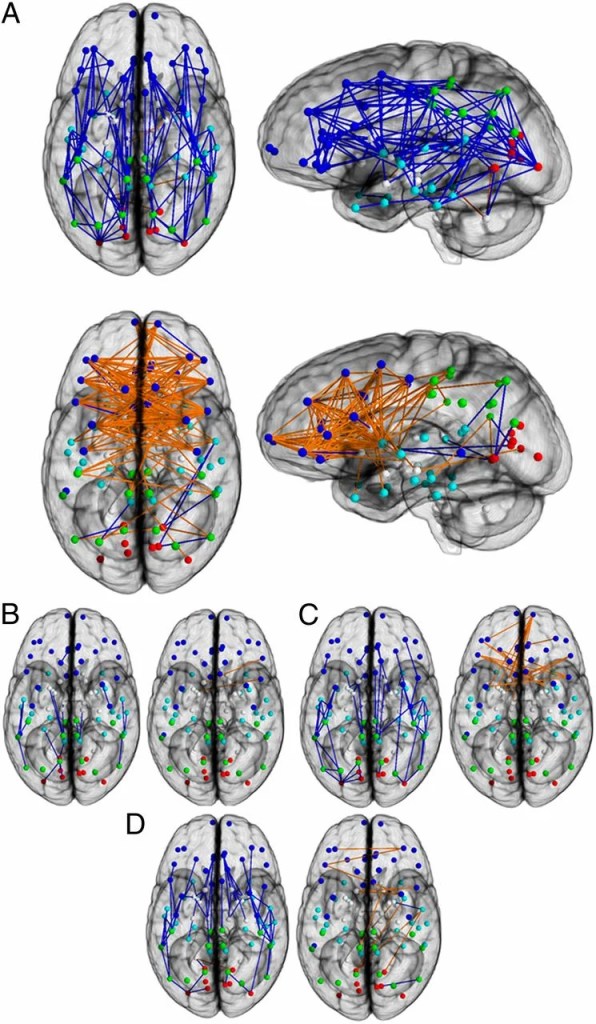

The first source of consideration is a large study from 2013 by Madhura Ingalhalikar and colleagues that focused on the structural connectome within the brain of both males and females. This study included 949 youths ages 8 to 22 years old with 428 being male and 521 being female. The researchers used diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) to examine the participants brains to examine the interactions among regions of the brain while computing a structural connectome of these interactions. What the researchers discovered is that there is a significant sex difference between male and female brains that suggested fundamental differences in connectivity patterns between the two. This study utilized available data that was acquired through the Institutional Review Board approval from both the University of Pennsylvania and the Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania. The data was acquired through approval which requires informed consent from both the child involved and their parents. They also published the data which requires approval and informed consent both of which was accomplished, and thus they followed the necessary ethical guidelines of the American Psychological Association (APA) that would have been required for this study (APA, 2017).

Noticeable differences include inter-hemispheric and intra-hemispheric connections. They found that male brains tend to develop in manner that facilitates intra-lobe and intra-hemispheric connections. This type of connectivity produces neural networks that are transitive, modular, and discrete. Females, on the other hand, showed greater inter-hemispheric connectivity that allows for greater efficiency in the integration of the analytical and sequential reasoning modes of the left hemisphere with the intuitive and spatial features of the right hemisphere. The behavioral implications of these connectome differences between the sexes have been revealed in behavioral studies mentioned in conjunction with the results of this study that include females outperforming males on attentional tasks, word and face memory, and social cognition tests, whereas males outperformed females on tasks relating to spatial processing and motor and sensorimotor speed (Ingalhalikar et al., 2013).

Source 2

The second source involves another large study conducted by Stuart J. Ritchie and colleagues in 2018 that examined the structural and functional aspects of male and female brains. This study used data from 5216 United Kingdom participants wherein they examined the MRI data on participants brains that included subcortical region volume, density, and surface area; white matter density; and resting-state connectivity. The researchers also utilized cognitive testing results that were acquired at the same time as the scans. The significant findings of neuroanatomical differences were that of brain volume, surface area, cortical thickness, diffusion parameters, and functional connectivity. And again, just as the previous study, this study utilized preexisting data that was acquired through the approval of usage through the UK Biobank and the University of Edinburgh Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology (CCACE), as well as the informed consent of UK Biobank members, all of which follow the ethical guidelines for research presented by the APA (2017).

Regarding cortical volume and surface differences, males had larger volume and surface areas in comparison to females, however, females showed exhibited thicker cortices. Furthermore, these differences in volume and surface area were also found to mediate a vast majority of small sex differences in reasoning abilities. The researchers also found similar results as the first study mentioned previously wherein there was greater connectivity within the default mode network in females while males showed greater connectivity in the sensorimotor and visual cortices (Ritchie et al., 2018).

Source 3

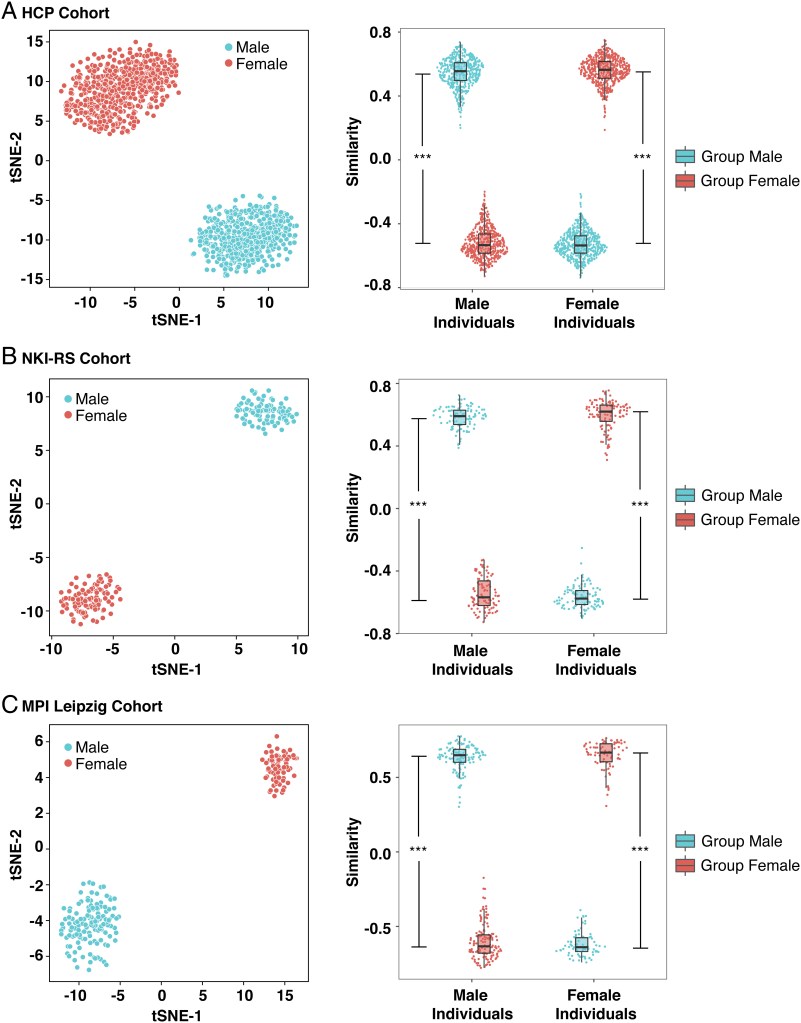

The last of the three studies was conducted by Srikanth Ryali and colleagues earlier this year in 2024 that utilized artificial intelligence and large multicohort functional MRI datasets consisting of 1,000 20-to-35-year young adults to help better understand sexual differences in organizational brain functionality. These differences were predominantly found in the organizational and functionality of the default mode network, striatum, and limbic network. These findings were not only replicable and generalizable, but they were also behaviorally relevant, and thus challenge the notion of a continuum in male-female brain organization. The researchers of this study obtained data upon approval from the Max Planck Institute of Leipzig, the Human Connectome Project, and the Nathan Kline Institute which also included informed consent on the part of participants. Their work was also supported and approved by the National Institute of Health, Transdisciplinary Initiative and Uytengsu-Hamilton 22q11 Programs, Stanford Maternal and Child Health Research Institute and NARSAD Young Investigator Award, and thus fulfill certain criteria of the APA code of ethics (2017).

Significant findings of this study included the replicability and generalizability of specific identifiable brain features between the sexes, and that these features help determine the cognitive profiles of the two sexes. Specific brain features that contribute to significant differences between males and females is that of the default mode network with the posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, and ventromedial prefrontal cortex playing the most discriminatory role. The default mode network is responsible for introspection, mind-wandering, and autobiographical retrieval, which may influence the sex-specific differences regarding self-regulatory behaviors, certain beliefs, and social interactions. Another notable difference between the sexes was found in the striatum and limbic networks. The striatum network is responsible for habit formation, reinforcement learning, and sensitivity to rewards, while the limbic system plays a role in correction of behavioral responses and expected reward value. These two systems help navigate an individual’s subjective pleasantness to experiences which may help explain differences in male and female hedonic experiences. On a final note, the differences laid out by the researchers were found to help predict cognitive profiles in males and females (Ryali et al, 2024).

Biological Mechanisms

When considering dimorphic characteristics of males and females, it is best to examine how both the body and mind interact to form the whole of the person. Two factors to be considered here are the effects of testosterone and estrogen, and sexual arousal and attraction. First, testosterone and estrogen play significant roles in the formation, stabilization, and motivational characteristics of both males and females. As mentioned previously, testosterone is the essential ingredient in helping determine a fetus’s destination as a male during gestation, and estrogen helps in the formation of both female reproductive parts and neuroanatomical features. Furthermore, levels of testosterone and estrogen throughout development are needed to maintain a certain level of homeostasis to provide a proper developmental trajectory, especially during the transitions of puberty (Garrett & Hough, 2022). Although testosterone levels gradually decline following the age of 30 for men, and both testosterone and estrogen decline during menopause for women, maintaining a level of homeostasis throughout most of one’s adult life is essential for both physical and mental health (Maattanen et al., 2021; Tsujimura, 2013; Lizcano & Guzman, 2014).

Next, not only do testosterone and estrogen play a vital role in overall mental and physical health and well-being, but they also influence sexual arousal and attraction. Testosterone influences male sexual drive (Nguyen et al., 2022), and in females to a lesser extent. Both estrogen and oxytocin play a larger role in female sexual arousal as well as orgasmic intensity and pleasantness (Garrett & Hough, 2022). Not only do these hormones help moderate male and female sexual arousal, but they also help direct and motivate the partners in which to copulate. For females, estrogen levels help dictate perceived attractiveness in potential mates, especially during ovulation. During this phase of the menstrual cycle when estrogen levels are at their peak, females often desire more masculine counterparts with features that are indicative of higher circulating testosterone levels (Gildersleeve et al., 2014). On the opposite side, testosterone helps dictate perceived attractiveness in male mating selection strategies with an increased focus on more feminine characteristics such as large eyes, neotenous features, petite stature, and smaller jaws (Bird et al., 2016). These dimorphic qualities are, at least in part, due to the effects of natural and sexual selection that have helped our species dimorph into two complimentary components of the overarching landscape of reproductive success and survival of the species.

Natural and Sexual Selection

Both natural selection and sexual selection have played a significant role in sexual dimorphism in the human species (Lassek & Gaulin, 2022; Stanyon & Bigoni, 2014). First, according to William Lassek and Steven Gaulin (2022), natural selection could potentially account for the dimorphism, especially physically, between males and females. This is evident in the physique differences between males and females, especially during the more primitive times of our development wherein males went out and hunted large, mobile game that required both strength and endurance, while females foraged locally and cooked the foods provided by the males. This energy expenditure demanded to accomplish daily hunting expeditions as well as carrying game that was killed, sometimes miles away, caused a larger adaptive feature for males compared to females. As this traditional practice was carried out over the course of millions of years, the adaptive morphological differences continued to expand.

Next, and as mentioned in the introduction, sexual selection was a mating strategy that has allowed for increased variations in both biological and neuroanatomical between males and females as females often sought out larger, more muscular counterparts that featured wider jaw width and increased strength which is an indicator of increased testosterone and overall health and vitality. Females were often driven towards finding mates that only possessed such traits, but that could also utilize them as was demonstrated through male-male competition for potential mates, as well as hunting success. Males, too, played a role in mate selection, however, minor in comparison to their counterparts, wherein they often sought out more “feminine” mates that presented neotenous and juvenile facial features, and larger hip-to-waist ratio which is an indicator of higher estrogen levels, and again, increased health and vitality, especially regarding childbearing (Puts, 2013). Interestingly, these same perceived attractive biological features in the dynamics of mate selection are still present in modern society pair bonding (Garza et al, 2016), although the effects have become more subtle in their application due predominantly to modernization and increased equality (Brooks et al., 2010), and the birth control pill, among other factors (Gori et al, 2014).

According to Stanyon and Bigoni (2014), these evolutionary selective mating strategies helped further drive the already prevalent neuroanatomical and behavioral differences among males and females that includes differences found within aggressive behavior, empathy and social skills. For instance, the propensity for aggressive behavior that is predominantly found among males that was instigated via male-male competition for mates is evident within the size of the neuroanatomical structures of the amygdala, mesencephalon, and diencephalon that are all positively correlated with the degree of male competition, along with a reduction in the size of the septum. Furthermore, increased empathetic tendencies and social skills found among females appears to be a consequence of sexual selection and pair bonding relationships along with its resultant formation of larger intergroup social dynamics that are evident further down the line of human evolution. The neuroanatomical evidence for higher capacity for empathy and social bonding among females is found within the increased density of gray matter found within the left-hemisphere that is involved in affiliation, social bonding and empathy.

Conclusion

As presented, sex differences do emerge both within both the physiology and neuroanatomy of males and females, and these differences are the result of contributing factors such as natural selection and sexual selection. Natural selection has helped humans evolve through the processes of selection pressure found within the environment that include such things as climate change, cooking, tool making, and pair bonding. These factors have helped shape humans both physiologically and cognitively in varying ways. Furthermore, as humans evolved and began to pair bond and cooperate within and between sexes, role playing in the form of male hunting and female gathering helped shape these sex differences that favor a larger physique for males and smaller physique for females. These role-playing effects also helped contribute to the neuroanatomical features of the brain as well wherein males acquired visual spatial skills that appear to have been the byproduct of being on the hunt and building tools and structures. On the other hand, females role-playing afforded them the essential skills of verbal communication and cooperation along with nurturance that enabled them to better care for social lives within the home and village or camp (Lassek & Gaulin, 2022).

Sexual selection has offered its adaptive morphological effects through male and female selective features that favored certain qualities that were dimorphic in nature, and yet also signaled health and vitality. Females often sought out males that were larger in stature with a more muscular build indicative of higher circulating testosterone that provided protective benefits and higher hunting success rate that generally accompanied such features. Males, on the other hand, often sought females that were more petite in stature and neotenous in appearance that indicated higher estrogen levels and fertility. As these selective processes continued through the evolutionary pathway from homo erectus approximately 2 million years ago until recent times, sexual dimorphic qualities continued to persist.

The evidence for such differences between the sexes, especially regarding the brain, was quite evident within the three studies provided wherein substantial differences emerged between male and female brains. The first study highlighted differences that were found using diffusion tensor imaging that revealed not only differences within certain regions of the brain between the sexes, but differences in the connectome between these regions. This difference in connectivity showed that males and females utilized different parts of the brain that helped explain differences in both behavior and perception. Another significance of this study was the fact that they utilized data from males and females during their developmental years, ages 8 to 22 years of age (Ingalhalikar et al., 2013). The second study went on to reveal how subcortical regions of the brains between males and females were different that included brain volume, surface area, cortical thickness, diffusion parameters, and functional connectivity. These differences are important to note as, again, they are often exhibited in behavioral and perceptual processes (Ritchie et al., 2018). The third and final study examined revealed an even deeper understanding of the differences between male and females by utilizing the latest technology such as AI to examine differences in both structural composition and connectivity. This study highlighted substantial differences in each of these factors that were both replicable and generalizable, and that challenges the idea of a female and male continuum of cognition that is currently being promoted (Ryali et al, 2024).

On an ending note, as technology advances and is utilized to help map out the human brain, more evidence might be found that helps shed light not only the history of humanity and the differences within, but also where humanity might be heading. These discovered differences should not be a discriminatory marker that undermines differences between the sexes but should rather be a beacon of information that highlights diversity among the human species. If utilized properly in a cooperative manner, just as the primitive ancestors of the past, humanity could continue its trajectory of progress towards a future of endless possibilities wherein sex differences are celebrated in an egalitarian manner that promotes all to achieve whatever it is that they set their minds on.

References

American Psychological Association (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. https://www.apa.org/ethics/code

Beau, E. (2024). Minor differences in male and female brains. Medium. https://ellebeauworld.medium.com/ive-said-more-than-once-that-there-are-minor-differences-in-male-and-female-brains-one-of-them-bb7ea3139f9b

Bird, B.M., Welling, L.L.M., Ortiz, T.L., Moreau, B.J.P., Hansen, S., Emond, M., Goldfarb, B., Bonin, P.L., Carré, J.M. (2016). Effects of exogenous testosterone and mating context on men’s preferences for female facial femininity. Hormones and Behavior, 85, 76-85, ISSN 0018-506X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2016.08.003

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2021, April 29). biology summary. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/summary/biology

Brooks R., Scott I.M., Maklakov A.A., Kasumovic M.M., Clark A.P. & Penton-Voak I.S. (2011). National income inequality predicts women’s preferences for masculinized faces better than health doesProc. R. Soc. B.278810–812 http://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2010.0964

Garrett, B. & Hough, G. (2022). Brain & behavior: an introduction to behavioral neuroscience 6th edition. Sage Publications, Inc. https://capella.vitalsource.com/reader/books/9781544373454/epubcfi/6/10[%3Bvnd.vst.idref%3Ds9781544373447.i30]!/4

Garza, R., Heredia, R. R., & Cieslicka, A. B. (2016). Male and Female Perception of Physical Attractiveness: An Eye Movement Study. Evolutionary Psychology, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/1474704916631614

Gildersleeve, Kelly & Haselton, Martie. (2014). Do Women’s Mate Preferences Change Across the Ovulatory Cycle? A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychological bulletin. 140. 10.1037/a0035438. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260376815_Do_Women’s_Mate_Preferences_Change_Across_the_Ovulatory_Cycle_A_Meta-Analytic_Review

Gori, A., Giannini, M., Craparo, G., Caretti, V., Nannini, I., Madathil, R., & Schuldberg, D. (2014). Assessment of the relationship between the use of birth control pill and the characteristics of mate selection. The journal of sexual medicine, 11(9), 2181–2187. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12566

Ingalhalikar, M., Smith, A., Parker, D., Satterthwaite, T.D., Elliott, M.A., Ruparel, K., Hakonarson, H., Gur, R.E., Gur, R.C., Verma, R. (2014). Sex differences in the structural connectome of the human brain, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.111 (2) 823-828, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1316909110

Larsen, M. (2023). Pair-Bonding: In Human Evolution. 10.1007/978-3-031-08956-5_1684-1. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/367470468_Pair-Bonding_In_Human_Evolution

Lassek, W. D., & Gaulin, S. J. C. (2022). Substantial but Misunderstood Human Sexual Dimorphism Results Mainly From Sexual Selection on Males and Natural Selection on Females. Frontiers in psychology, 13, 859931. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.859931

Lizcano, F., & Guzmán, G. (2014). Estrogen Deficiency and the Origin of Obesity during Menopause. BioMed research international, 2014, 757461. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/757461

Määttänen, I., Gluschkoff, K., Komulainen, K., Airaksinen, J., Savelieva, K., García-Velázquez, R., & Jokela, M. (2021). Testosterone and specific symptoms of depression: Evidence from NHANES 2011-2016. Comprehensive psychoneuroendocrinology, 6, 100044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpnec.2021.100044

Nguyen, V., Leonard, A., Hsieh, T.C., (2022). Testosterone and Sexual Desire: A Review of the Evidence. Androgens: Clinical Research and Therapeutics, 3(1), 85-90. 10.1089/andro.2021.0034. https://liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/andro.2021.0034

Puts, D.A. (2010). Beauty and the beast: mechanisms of sexual selection in humans. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31(3), 157-175, ISSN 1090-5138, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.02.005

Ritchie, S.J., Cox, S.R., Shen, X., Lombardo, M.V., Reus, L.M., Alloza, C., Harris, M.A., Alderson, H.L., Hunter, S., Neilson, E., Liewald, D.C.M., Auyeung, B., Whalley, H.C., Lawrie, S.H., Gale, C.R., Bastin, M.E., McIntosh, A.N., Deary, I.J. (2018). Sex Differences in the Adult Human Brain: Evidence from 5216 UK Biobank Participants, Cerebral Cortex, 28(8), 2959–2975, https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhy109

Ryali, S., Zhang, Y., de los Angeles, C., Supekar, K., & Menon, V. (2024). Deep learning models reveal replicable, generalizable, and behaviorally relevant sex differences in human functional brain organization, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.121 (9) e2310012121, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2310012121

Stanyon, R. & Bigoni, F. (2014). Sexual selection and the evolution of behavior, morphology, neuroanatomy and genes in humans and other primates. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 46(4), 579-590, ISSN 0149-7634, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.10.001

Timmermann, A., Raia, P., Mondanaro, A., Zollikofer, C.E.P., de Leon, M.P., & Yun, K.S. (2024). Past climate change effects on human evolution. Nat Rev Earth Environ 5, 701–716. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-024-00584-4

Tsujimura A. (2013). The Relationship between Testosterone Deficiency and Men’s Health. The world journal of men’s health, 31(2), 126–135. https://doi.org/10.5534/wjmh.2013.31.2.126

Tuttle, R. H. (2024). Human evolution. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/human-evolution

Wrangham, R. (2009). Catching fire: how cooking made us human. Basic Books.

Zitzmann M. (2020). Testosterone, mood, behaviour and quality of life. Andrology, 8(6), 1598–1605. https://doi.org/10.1111/andr.12867